Did you know cartoonists were on Nixon's enemies list? Or that LBJ prevented a cartoonist from getting a medal when he made a cartoon against the Vietnam War? Today we talk about the history of editorial cartoons and political satire, from "Join or Die" to the Obama fist bump, from Thomas Nast to Jimmy Kimmel. Our guide is New Yorker cartoonist Tom Toro, author of And to Think We Started as a Book Club.

Cartoons!

Transcript

C101_Making fun of politicians.mp3

Archival: It borders on being, you know, prejudicial religiously. I don't see the satire in it. I don't think that the rest of the country that looks at it will see any sort of satire. And I don't think I don't think there's anything funny about it at all.

Archival: John Heilemann, your thoughts on your rival magazine?

Archival: I think it's brilliant. And it's right down the middle of the plate for the New Yorker's audience. I think everybody who looks at that magazine and reads it understands that it is, in fact, satire. I think the only way in which these kind of cartoons work is when they play to an existing perception that's out there in the world. And that is, in fact, as the New Yorker has [00:00:30] been arguing all day long, that's what they're making fun of.

Nick Capodice: You're listening to Civics 101, I'm Nick Capodice.

Hannah McCarthy: I'm Hannah McCarthy.

Nick Capodice: And today we are talking about the power of laughter.

Tom Toro: Throughout American history, the long and proud tradition of political cartooning. I mean, like the presidents have been explicit targets from the from the beginning.

Hannah McCarthy: Is that Tom Toro, did you talk to Tom?

Nick Capodice: I did, everybody, this is Tom [00:01:00] Toro.

Tom Toro: I am Tom Toro. I'm a cartoonist for The New Yorker magazine and various other outlets.

Hannah McCarthy: Now, Tom is not just any cartoonist. He has a special place in our hearts because he illustrated our book, A User's Guide to Democracy How America Works. And he did such a good job.

Nick Capodice: He did. And he has a new collection of his New Yorker cartoons out right now called. And to think we started as a book club.

Hannah McCarthy: What is that title all about? Is that a caption from a cartoon?

Nick Capodice: It is. It's it's what a bank robber is saying to the other [00:01:30] folks in his crew.

Hannah McCarthy: Now, Nick, I think you're going to know what I'm talking about. We're running into a little bit of a problem here.

Nick Capodice: We are. I am way ahead of you, Hannah. Tom thought about this, too.

Tom Toro: Nothing is more engaging than verbally describing a cartoon to a podcast audience.

Archival: It's funny. It's a pig at a complaint department.

Archival: Yeah. And he's saying, I wish I was taller. See, that's his complaint.

Nick Capodice: So with the caveat emptor [00:02:00] here, radio not being the most apt medium to explore illustrations, we're going to do our best. Politicians have a deep history of despising those who make fun of them. Specifically cartoonists. And maybe the most famous of all is a fellow named Thomas Nast. Do you know Thomas Nast?

Hannah McCarthy: I do, I don't have a framed Harper's Weekly on my wall for nothing. He was a cartoonist in the late 1800s, and he was [00:02:30] responsible for our modern day depiction of Santa Claus, wasn't he?

Nick Capodice: He was. He's credited with the first illustration of what we now think of as Santa in 1863. But as you know, he is perhaps even more famous for parodying one of the great villains in New York politics.

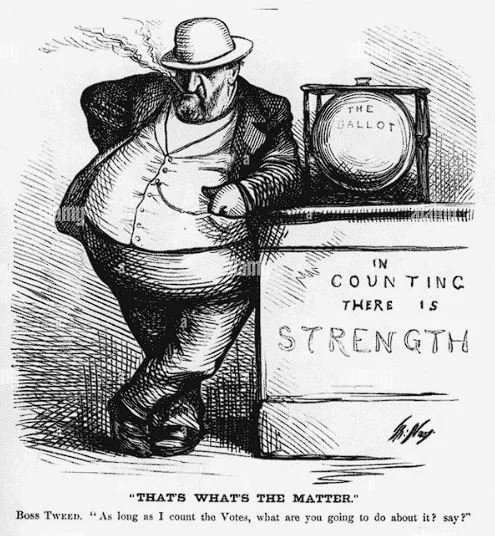

Tom Toro: The political powerhouse that he mostly targeted was who ran New York at that time. Uh, Boss Tweed. Boss Tweed pretty much put Thomas Nast on his blacklist, you know, and he got really upset whenever [00:03:00] he was made fun of in the in the New York papers.

Nick Capodice: William Meager Tweed, also known as Boss Tweed, ran something called Tammany Hall.

Hannah McCarthy: By the way, listeners, there was no physical hall, no actual building called Tammany Hall. Tammany Hall was a political machine in the 1800s.

Nick Capodice: Right? Though I think there is a bar in Manhattan called Tammany Hall. That is not what we're talking about here. Tammany Hall was a relentlessly corrupt group that [00:03:30] bought politicians and newspapers and judges. They rigged elections. They courted immigrant voters in particular, all to ensure that they were reelected in perpetuity. So Thomas Nast drew dozens of cartoons pointing out Tweed's corruption, and it made Tweed furious.

Tom Toro: And finally, an aide went up to Boss Tweed and said, why are you so upset over these cartoons? Why are you so? Why is this cartoonist bother you so much? You're also getting bad, bad articles written about you. There's there's bad press [00:04:00] about you. Why are this fixation on Thomas Nast? And apparently, Boss Tweed said, my constituents can't read, but they can see pictures, damn it. So despite the low opinion he had of his constituents, I think that sort of really is a great example of like the power of cartoons through their immediacy, the way they can crystallize an idea, the way they can grab attention in a very unique and particular way embedded among newspapers or an ad. We encounter them on social [00:04:30] media. There's like a clarity to cartooning that I think is threatening to people whose goal is to maybe obscure the truth or to, like, put their own spin on events. And, you know, you're hitting the right mark. When people in positions of authority are fixated, like on cartoons, are really upset by them, you know, you know, you're making an impact.

Nick Capodice: Funny side story I can't help but tell you. Hanna. Boss Tweed was finally arrested for embezzling $6 million. He escaped jail and fled to Spain. And he was arrested in Spain [00:05:00] because Spanish authorities were reading a newspaper with one of Nast's comics in it.

Nick Capodice: Like this kind of looks like the guy from the cartoon.

Tom Toro: And then later on, you know, Nixon had a blacklist that included political cartoonists, those cartoonists who rankled, you know, Bush during the Iraq War.

Hannah McCarthy: Wait, a cartoonist made Nixon's enemies list?

Nick Capodice: Yes. Several did. One was Paul Conrad. He was an editorial cartoonist for the LA times. Though I do want to be fair, Nixon's [00:05:30] list was expansive, hundreds of names. It had a lot of celebrities like Paul Newman, Steve McQueen, June Foray. Do you know June Foray?

Hannah McCarthy: I have no idea who that is.

Nick Capodice: She is the voice of Rocky the Squirrel from The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show.

Archival: Now, here's something we hope you'll really like.

Hannah McCarthy: Why on earth would she on the enemies list?

Nick Capodice: Uh, she testified before the Joint Economic Committee that inflation was out of control, and Nixon [00:06:00] did not like that. But it wasn't just President Nixon who clashed with cartoonists. Herbert Block, known as Herblock, also happened to be on Nixon's enemies list. Herbert Block was going to win the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon Johnson in 1965, but after Herblock published an anti-Vietnam cartoon, Johnson withdrew the medal.

Hannah McCarthy: Okay, so I get Tom's point about how cartoons can really skewer people [00:06:30] in power, and you know how those people don't like it. But I also wonder if they feel, you know, like personally attacked, if they feel kind of bullied. Presidents are rarely portrayed as being particularly attractive in cartoons. Do you think that bothers them?

Nick Capodice: Yeah, I wonder about that. Have you ever been impersonated, Hannah?

Hannah McCarthy: It's really only my friend Josh who, um. I have a tendency to reference the fact that my father is [00:07:00] really good at fixing things and building houses. And anytime I even start to say something, Josh will be like, I'm Hannah McCarthy, and wouldn't my father just sweep right in and fix it all up? So, yeah, that's, um, that's Josh's impression of me.

Nick Capodice: To be fair, you sound nothing like that. Uh, in elementary school, during a particularly rough phase in my childhood, I was nicknamed, according to my calculations. Oh, yeah? And people would say, I'm. I'm Nick, and I'm a fan of prestidigitation and [00:07:30]Legerdemain, and I deeply enjoy that in hindsight. But at the time, in fourth grade, I was pretty wrecked. And what wrecked me was that it took stuff about me that's actually kind of true and pump that stuff up to the max. And this is what political cartoonists do every day.

Tom Toro: Caricature is one of the key components of cartooning, right? Caricature relies upon an audience's familiarity with the subject. Right? Because when you're exaggerating [00:08:00] or lampooning. And so there's almost no one more, you know, high profile in a society than the leader of that society. So when you're doing caricature, not only is it sort of incumbent upon cartoonists to make fun of those in positions of power and to question them and to sort of push, transgress as much as possible? Um, but you also have to do it in a way that's recognizable. An audience, knowing what the president looks like helps you as a cartoonist, because then you can do your rendition of that and exaggerate their physical characteristics, [00:08:30] like famously, Obama with his ears, you know, Bush with his like, like like little pointy nose and his little neck. And so, like, you can do that sort of thing. And I think that's because, uh, you're playing off of more reference points that the audience is familiar with.

Nick Capodice: All right. We're going to talk a little bit more about making fun of those in power, as well as some of the most famous political cartoons in US history, right after a quick break.

Hannah McCarthy: But before that break, if you want to support public radio and shows like Civics 101, please consider donating to our show. There's [00:09:00] a link in the notes for this episode, and especially since the congressional recission of funds allocated for public radio stations like ours. It helps us a great deal.

Nick Capodice: Sure does. We are back. We are talking parody and satire in the political world, specifically in the realm of political cartoons.

Hannah McCarthy: All right, Nick, you got a Hall of Fame of the greatest, most impactful cartoons in US history. [00:09:30]

Nick Capodice: I certainly do. I'm going to put pictures to each of these on our website. I will put a link in the show notes if any of you want to look along as you listen.

Hannah McCarthy: Just not if you're driving.

Nick Capodice: Not if you're driving, please. Not if you're driving. All right, so the first on my list, which is maybe the most famous political cartoon ever drawn, came from before we were a country. You know what I'm talking about here, Hannah?

Hannah McCarthy: You're talking about a snake.

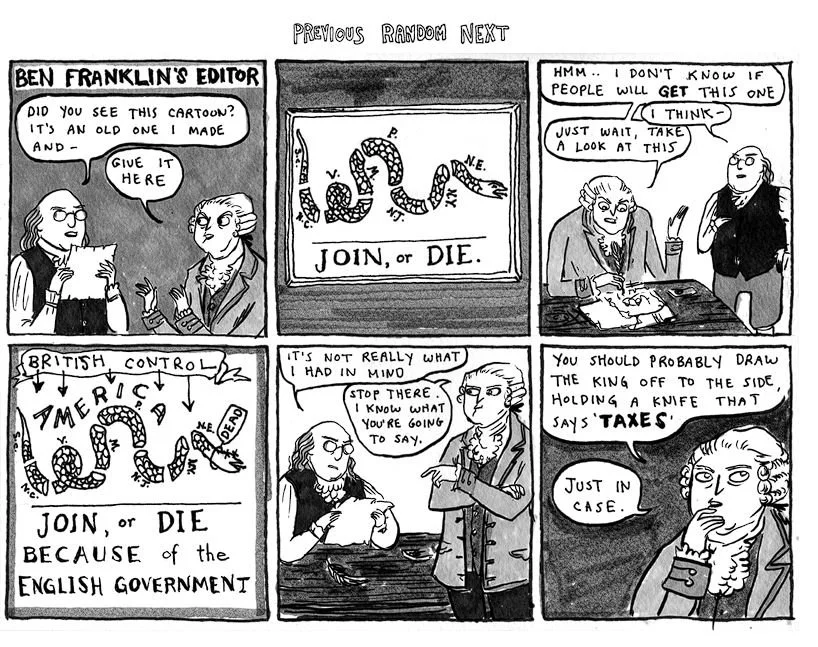

Nick Capodice: In 1754, Benjamin [00:10:00] Franklin published a cartoon in the Pennsylvania Gazette. It was a depiction of a snake cut up into eight pieces, each piece having the name of a different colony on it, and below the ominous words join or die. Now, this cartoon was originally written to inspire the colonies to get together in the wake of the French and Indian War, to manage money and defenses, but pretty soon it took on an entirely new meaning.

Hannah McCarthy: Yeah, [00:10:30] the Join or die motto had a big resurgence during the American Revolution. I recently learned that it was printed in a New York newspaper every single week for a year.

Nick Capodice: Really?

Hannah McCarthy: Oh, yeah.

Nick Capodice: Actually, one of my favorite modern day cartoonists, Kate Beaton. She has a really good one of Benjamin Franklin being hassled by his editor. The editors, like, maybe you should write British control on top of the snake and have King George on the side with a knife that says taxes. All right, I got one more [00:11:00] oldie but a goodie, Hanna. It is a pair of cartoons by the aforementioned Thomas Nast. One is called Third Term panic and the other one are.

Hannah McCarthy: What.

Nick Capodice: I am hesitating to say. The title of this cartoon, Hannah. Because teachers sometimes play our episodes in class, but it's the title of a cartoon from the 1800s, the title being a Fine Ass Committee.

Hannah McCarthy: Uh, [00:11:30] okay, so it's a donkey.

Nick Capodice: It is.

Hannah McCarthy: And does third term panic maybe have an elephant in it?

Nick Capodice: Yep. Sure does.

Hannah McCarthy: Are these the first depictions of the donkey and the elephant representing the two parties?

Nick Capodice: They are sort of the Democrats as a donkey goes all the way back to Andrew Jackson. But Nast is entirely responsible for creating the GOP elephant symbology. And I think it's kind of funny because in the cartoon, the elephant is clumsily smashing the planks of his own platform.

Hannah McCarthy: Okay, [00:12:00] so not something that you would necessarily want to tie to your party. And you know what? Thinking about it, maybe not donkeys either.

Nick Capodice: That's just the way it goes, Hannah.

Nick Capodice: All right. Last cartoon. And this one happened in our lifetimes, and I had almost forgotten about it, but it was a big deal here. To break it down again is our friend, colleague, and New Yorker cartoonist Tom Toro.

Tom Toro: Barry Blitt came to national attention during the Obama years. I think it was during Obama's first presidential [00:12:30] run, when he did a cover depicting Michelle Obama and Barack Obama in the Oval Office, fist bumping, and Obama was in, like, traditional sort of Arab garb. And Michelle was dressed up like, you know, a radical Islamist with like an AK 47 over her shoulder. And they were fist bumping.

Archival: Barack Obama's campaign is calling it tasteless and offensive. It's a satirical New Yorker magazine cover showing Obama dressed as a muslim. His wife is a terrorist.

Archival: If this were on the cover of time [00:13:00] magazine or Newsweek, I would be more likely to think that this would be perpetuating false beliefs.

Tom Toro: And it was meant to sort of portray the stereotypes that were being thrown at them, or the fear the conservatives had around like. They were actually like a secret cell coming to like, take over our country. You know, like they were like a terrorist cell. David Remnick, the editor, had to actually get on, you know, cable TV and like, explain the cover.

Archival: The intent of the cover is to satirize the vicious and racist attacks and rumors and misconceptions about the Obamas that have [00:13:30] been floating around in the in the blogosphere and are reflected in public opinion polls.

Hannah McCarthy: So it wasn't saying the Obamas were what the cartoon depicted. It was making fun of people who thought they were.

Nick Capodice: Yeah. And I gotta mention shortly before this cartoon, when Barack Obama won the Democratic nomination, he gave Michelle Obama a fist pound, and a commentator on Fox News named E.D. Hill said this.

Speaker16: A fist bump, a pound, a terrorist [00:14:00] fist jab. The gesture everyone seems to interpret differently.

Hannah McCarthy: Wow.

Nick Capodice: Yeah. And the cartoonist Blitt was excoriated in the press for this cartoon. But that is the world of comedy. Comedy is often about going just a little bit too far.

Tom Toro: There's a great metaphor that the editor who I broke in under Bob Mankoff, who has since retired, he has this metaphor for humor and how humor works, where it's like, imagine [00:14:30] you're at a zoo and there's a lion behind the bars of the cage. That's a good zoo. Now imagine the lions not there, and it's just the empty cage. That's a bad zoo. But now imagine the lion is out of the cage and the bars are behind the lion. And the lion is actually on your side of the cage. That's a worse zoo. Right. So it's like, where is that line? Right. You want there to be some sense of not necessarily aggression, but transgression, right. Like you're pushing [00:15:00] the boundary. And so it's about finding for your audience in the context that you're working inside of. Like where do those cage bars have to be. Because you want there to be a sense of danger. You want there to be a sense of subversion to your humor, but if you're too aggressive, then your message gets lost just in the offensiveness. It's almost being offensive for the sake of being offensive, and it's not being offensive for the sake of like, making a point or making an argument. You're just trying to rankle sensibilities. But it's like finding out where that lion belongs and [00:15:30] where that cage bar belongs is like the balancing act that we're always, you know, undergoing as as a cartoonist and humorists.

Hannah McCarthy: Are there any unspoken rules in the world of political cartoons? Are there things you just don't do?

Nick Capodice: Yeah, there are. And of course, if we're talking the nebulous world of comedy, there are going to be exceptions to everything. And these rules are broken every day. But the number one rule is don't punch down, punch up. And to sort of encapsulate what that means, the satirist Molly Ivins, whose [00:16:00] books I loved as a kid, she once said, quote, satire is traditionally the weapon of the powerless against the powerful. I only aim at the powerful when satire is aimed at the powerless, it is not only cruel, it is vulgar and tied to this punch up, no matter who is in charge.

Tom Toro: To be just as critical of Democratic administrations as you are as Republican administrations. And when that comes and goes, [00:16:30] then I start to be suspicious of your project as an artist, right? If you're like, soft pedaling stuff the Republican administration does, and you're sort of overemphasizing mistakes that a Democratic administration makes, then you're kind of on board with the particular political party. And I think it's it's incumbent upon artists and cartoonists to be equal opportunity offenders. You have to be just as strident against all powers that be. And it's also deeply scary. I mean, it's it's scary to go up against any regime [00:17:00] of censorship. We have examples all over the world of cartoonists working under actual authoritarian regimes and actual oppressive regimes who have been jailed, killed, have had to flee. History has shown us time and time again that when authoritarians take control, the first thing they do is try to silence humorists, because there's something about it which is like there's the sort of overused metaphor of the canary in the coal mine. And, [00:17:30] you know, cartoonists get threats of violence all the time. In particular in our country, like women, political cartoonists are especially the targets of like, if not outright threats, like sort of disproportionate online vitriol. Um, I know Anthony, who used to work for the Washington Post before she, you know, quit in protest from one of her cartoons getting cut.

Nick Capodice: Did you see that cartoon, Hannah?

Hannah McCarthy: I think so. This was the one of tech oligarchs worshiping at the feet of Donald Trump holding bags of money.

Nick Capodice: Yeah, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Sam [00:18:00] Altman, all of whom pledged to make massive donations towards Donald Trump's inauguration.

Tom Toro: The Washington Post, which is now owned by Jeff Bezos, cut that cartoon. They killed it. They didn't want to run it. And so she quit in protest and ended up, you know, posting. So and they actually made the cartoon more famous than it would have been otherwise, because then she posted it and it went viral online. But I remember talking to her one time and she and she's an equal opportunity defender. I know she did cartoons against Obama as well, but her Trump stuff started to get a lot of online vitriol directed [00:18:30] at her. Um, so cartoonists are sort of the targets of threats and doxing and that sort of thing just as much as, you know, political commentators across the spectrum.

Hannah McCarthy: So, Nick, moving out of the cartoon world into the humor world more generally. You talked to Tom the week after Jimmy Kimmel was taken off the air.

Archival: That's right. This is fast developing this afternoon, Jake, amid pressure from the Trump aligned FCC. And in the past few minutes, ABC [00:19:00] confirmed to CNN that Kimmel's show will be off the air indefinitely.

Nick Capodice: Yeah, I talked to him literally the day after Kimmel show went back on at ABC.

Hannah McCarthy: Did Tom have any thoughts about that?

Nick Capodice: Well, unsurprisingly he he did. We talked about Jimmy Kimmel's monologue on the night of his return, and I think the whole Jimmy Kimmel situation is one that all comedians care deeply about.

Tom Toro: We're not very important at the end of the day. Will the world end [00:19:30] if Jimmy Kimmel is no longer allowed to make jokes on the air? Ultimately, no. Right. Like life will go on. It's not crucial to the existence of our civilization. And yet, by the very fact that it is relatively unimportant in the grand scheme of things, it makes it more scary that it would be the target of censorship. Right? Because why? Because you start there. And then where does it lead? Right. It's the first step toward a greater project of silencing bad stories. And I think that, you know, it's an indication [00:20:00] of it's more revealing of the nature of power than it is of the nature of the comedian. Right. If you're that sensitive toward jokes, then probably, you know, you do not believe in democracy in some fundamental way, right? If he is the target of censorship, then like, you know, then where do the rest of us stand?

Nick Capodice: Well, [00:20:30] that's it for political cartoons and cartooning. Today on Civics 101, check out Tom's new book. I've had a peek at it and it's hilarious. This episode was made by me Nick Capodice with Hannah McCarthy. Thank you Hannah. Our staff includes Marina Henke and our executive producer, Rebecca Lavoie. Music. In this episode from blue Dot sessions, Epidemic Sound and the great Chris Zabriskie. Civics 101 is a production of NPR, New Hampshire Public Radio.

Archival: Why [00:21:00] is it that the that the animals enjoy reading the email?

Archival: Well, Miss Benes, cartoons are like gossamer, and one doesn't dissect gossamer.

Archival: Well, you don't have to dissect it.