When this episode was recorded, gasoline prices in the US averaged $3.28 a gallon. Stickers of President Biden saying "I did that" decorated gas pumps across the country. What handles, if any, does a president have to lower the price of gas? How responsible are they for high prices?

Today we get to the bottom of the oil barrel with two specialists; Robert Rapier from Proteum Energy and Irina Ivanova from CBS News. They guide us through a purely economic, scientific, and historical analysis of the powers of the chief executive, from the 70s to now, and the price of gasoline.

Link to Robert’s article, How a President Can Impact Gas Prices

Link to Irina’s article, Can President Biden Do Anything to Lower Gas Prices?

Click here to find more charts of Civics 101 episodes from Periodic Presidents!

Transcript

presidents and gas 2.mp3

Archival: All righty, folks, check this out. You see that. That's all me. "I did that." Yeah, he did it. That's what's killing my business.

Nick Capodice: You ever see one of those, Hannah

Hannah McCarthy: And "I did that" sticker?

Nick Capodice: Yeah.

Hannah McCarthy: Yeah.

Nick Capodice: Would you describe it for me?

Hannah McCarthy: Yeah, it's just Biden pointing, the sticker says, "I did that" and people will slap it on, like the gas pump at a gas station.

Archival: Next [00:00:30] person who gets their gas and they they get sticker shock. They get to remember that. President Biden did that. Here we go. Right next to that four Dollar and sixty seven cents a gallon gasoline.

Nick Capodice: I was looking around for videos of these stickers at gas stations to make this episode, and you can buy them anywhere, by the way. One recent gas pump display I saw had three stickers. It had Joe Biden pointing and saying, I did that. And then a picture of Speaker of the House Nancy [00:01:00] Pelosi saying I helped. And then Vice President Kamala Harris saying, I just blank; the blank being a rude word I don't want to say on this podcast. And if we were like a hip, fast paced political talk show, we could make today's episode, Well, did he do that? Did Joe Biden make gas prices go up? And while we will answer that question today, we're going to frame it a bit differently because you're listening to Civics 101, I'm Nick Capodice,

Hannah McCarthy: I'm Hannah McCarthy,

Nick Capodice: And today we're talking about the president [00:01:30] and the price of gasoline. What is the relationship throughout American history between our chief executive and what we pay at the pump? And to start our journey, Hannah, I want to introduce you to Robert Rapier.

Robert Rapier: So, yeah, my name is Robert Rapier. I'm a chemical engineer. I work for Proteum Energy. We take oilfield flare gas and other supplies, and we convert that into hydrogen. On the side, I write for Forbes.

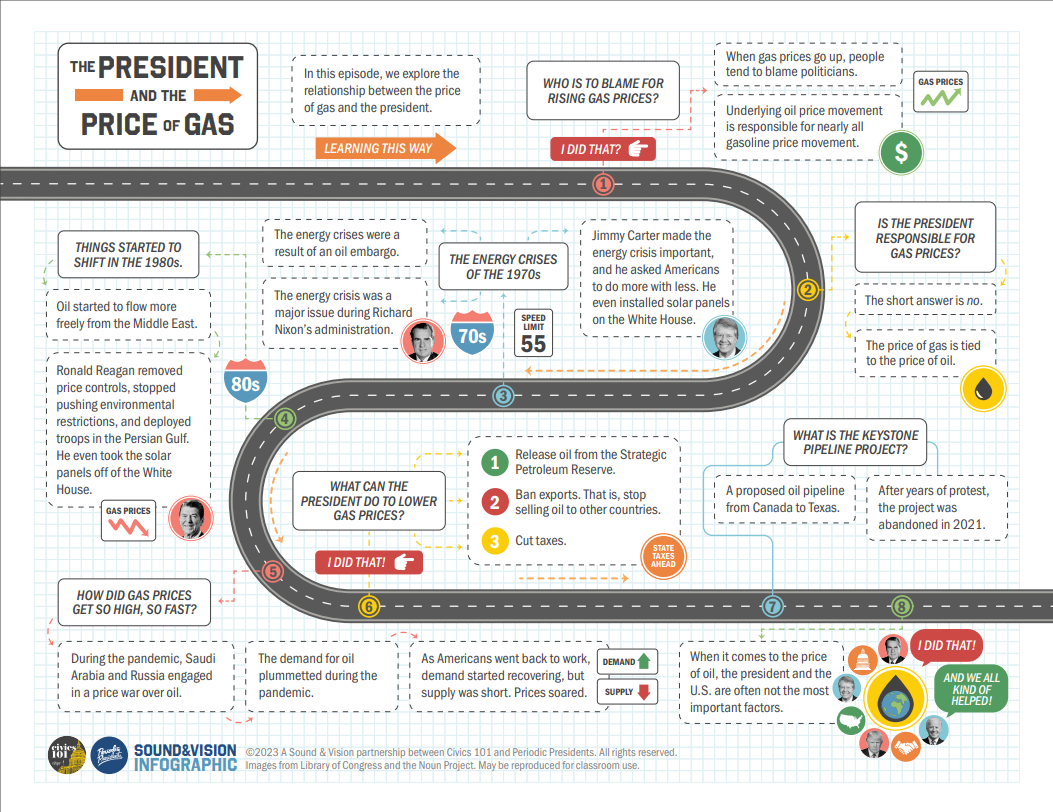

Nick Capodice: Just [00:02:00] to reiterate, Robert is not a political scientist. He has worked in engineering in the fuel and oil industry for about 30 years. And March of 2021 he wrote an article called "Who is to blame for rising gas prices?" And I spoke with him and he let me in on a little secret.

Go on.

He told me the name of the person actually responsible for high gas prices.

Hannah McCarthy: Who is it?

Nick Capodice: Yoweri Museveni. He's [00:02:30] the president of Uganda.

Robert Rapier: So a friend of mine that lives in Uganda, he wrote to me about, you know, a few months ago, and he said gas prices here are up 50 percent. And I said, Wow. I said, Who do people blame? And he said, our politicians. And I said, OK, so now we know who to blame for gas prices. Uganda's politicians.

Nick Capodice: He's [00:03:00] joking, I'm joking, we're all joking. Please don't go putting stickers on Ugandan gas pumps.

Robert Rapier: so I think that's, you know, it's universal. When gas prices go up, people blame the politicians. Basically, the underlying oil price movement is responsible for nearly all of gasoline price movement. So if you want to know why gas prices increase, it's almost always, well, oil prices increase. And what I said in that article is there are very few handles that a president [00:03:30] has to influence gas prices in the short term.

Hannah McCarthy: So what I'm getting here is that the short answer to is the president responsible for the price of gasoline is no.

Nick Capodice: Correct. It is no. We can end the episode right now.

Hannah McCarthy: Now this is such a touchy topic. Nick, what was the response to Robert's article?

Nick Capodice: It was not pleasant. The reason I reached out to him specifically was because his analysis was explicitly nonpartisan. I wanted to talk to someone who would [00:04:00] take the political fuel out of this debate.

Robert Rapier: Yeah, I try to do that. But people will still say, Oh, you're being political, and I say, No, I'm not. I'm just telling you what's happening. You can view it that way if you want. But I'm telling you what's actually happening. And I got a lot of nasty, nasty messages from people who were like, Oh, you must be an idiot. Any idiot can see that Biden became president, and then we had this big surge in gas prices. How could he not be responsible? And then people would say, How [00:04:30] can you spend all this stimulus money and not expect inflation? He canceled the Keystone Pipeline. How can you not see? And all these things? I mean, none of them. None of them have much of an impact on gas prices.

Nick Capodice: And I'm going to get back to the Keystone pipeline because that is relevant to this topic. But it's not just President Biden. These accusations have happened to whomever has been president when gas was expensive. But as Robert [00:05:00] said, the price of gas is ruthlessly firmly permanently tied to the price of oil.

Hannah McCarthy: Ok, like how tied?

Nick Capodice: I want to show you this graph, and I'm going to put it on our website if anyone wants to see it. Civics101podcast.org It is a chart of the price of oil and the price of gasoline in the U.S. since 1946.

Hannah McCarthy: Oh, they track almost exactly.

Nick Capodice: Exactly, yeah. And it is hard sometimes to look outside of our star spangled shell. But the [00:05:30] rise and fall of the price of gas in the U.S. over the years is the same in the U.K., Canada, Portugal, et cetera.

Hannah McCarthy: Ok, so yes, you've made it very clear that the price of gas mirrors the price of oil, but can you answer for me why it is so expensive right now in January 2022?

Nick Capodice: Yeah, but first I have to put this in the broader historical picture.

Irina Ivanova: People are really upset now because gas is over three dollars a gallon. You know, this does not even [00:06:00] compare to what was going on in the 70s.

Nick Capodice: This is Irina Ivanova, she's an economic reporter for CBS News, and she recently wrote an article called Can President Biden Do Anything to lower gas prices?

Irina Ivanova: Right now we have. We have gas. It's expensive, it's definitely hurting people. You know, we need our cars. And if you're on a tight budget, it hurts your budget. In the seventies, I mean, we we had like gas lines around the block.

Archival: This [00:06:30] gas line at one station on the Upper West Side ran from Ninety Sixth Street and West End Avenue, all the way up to one hundred and Second Street. This is unreal. Isn't this disgusting? Why doesn't anybody contact the president? Why is he letting this happen to us?

Nick Capodice: When I say energy crisis in the nineteen seventies, who's the first person that jumps into your mind? Who do people blame.

Hannah McCarthy: Jimmy Carter? No?

Archival: We face a problem, a problem with regard to energy heating. For example, this winter, just as we thought, we faced a problem [00:07:00] of gasoline this summer and the possibility of brownouts.

Nick Capodice: Carter popped into my head, too, but it started with Richard Nixon. The energy crises, plural, by the way, in the nineteen seventies were massive and complicated. They dominated the headlines. But to summarize. Are you familiar with OPEC, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries?

Hannah McCarthy: Isn't it a group of countries that produce a lot of oil and so they agree on prices and production so that we don't run out of oil and so the market is not wildly [00:07:30] unstable?

Nick Capodice: Absolutely. And there's also OAPEC, which is the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries. And a long story short, OAPEC created an embargo. They refused to sell oil to countries that had supported Israel in what is called the Yom Kippur War. The United States was one of the eight nations embargoed, and it was devastating.

Irina Ivanova: The U.S. didn't have domestic oil production at that point, or if they did it, it was really minimal. You know, we were importing oil mostly [00:08:00] from the Middle East. So there was this real sense of, you know, the U.S. being at the mercy of foreign powers and then the president not being able to to do anything about it. I mean, you know, what are what are what are you going to what are you going to do, say, like, Hey, guys, like create more oil, you know, it was a whole geopolitical crisis.

Nick Capodice: And gas wasn't just expensive after this embargo, there just wasn't enough of it.

Irina Ivanova: I mean, this is this is literally like, you need fuel. [00:08:30] You cannot get it. People had to fill their tank based on the number on their license plate. And then, of course, you had people swapping around license plates so that on this day it was only plates ending and even numbers could get filled up. On the next day, it was, you know, plates ending in odd numbers.

Nick Capodice: President Nixon established price controls on domestic oil. He asked gas stations to not sell gas on Saturday nights and Sundays. And Congress created the 55 mile per hour speed [00:09:00] limit on federal highways, which was the inspiration for Sammy Hagar's hard rock anthem. I can't drive 55.

Hannah McCarthy: The fifty five mile an hour speed limit was to control use of gas??

Nick Capodice: Gas consumption, absolutely, you save gas when you drive slower. This was the issue in the Nixon administration. In a poll conducted in New York, seventy six percent of people said [00:09:30] the energy crisis was the most important problem facing the country versus Watergate, which got about 15 percent. And then it was the issue in Gerald Ford's administration. And then Jimmy Carter made the energy crisis his own personal Waterloo. He gave speeches and how we all just have to use less gas. He installed solar panels on the White House. He asked Americans to just do more with less, which you can imagine was an extremely unpopular concept.

Archival: If we learn to live truthfully [00:10:00] and remember the importance of helping our neighbors, then we can find ways to adjust.

Nick Capodice: It was so unpopular that it was parodied by Archie Bunker in all in the family.

Archival: Bet you won't find none of them congressmen turning down their electric blankets tonight.

Nick Capodice: And then things started to shift in the 1980s. Oil started to flow more freely from the Middle East. Ronald Reagan came in, removed those price controls that Nixon and created stopped pushing Carter's automobile efficiency [00:10:30] standards, removed all environmental restrictions on local gas production and deployed soldiers in the Persian Gulf. And the last thing he did was to take the solar panels off the grid for the White House. Gas prices came down.

Hannah McCarthy: Wow. Ok. All of that history brings up the question from the beginning of this episode. Can a president or a Congress do anything to lower the price of oil and therefore gasoline? Are [00:11:00] there any executive powers that President Biden can use or has used?

Nick Capodice: There are sort of, and we're going to talk about three of the things a president can do to lower the price of gas, along with the breakdown of what's going on right now. And finally, how the Keystone XL pipeline is tied to all of this right after the break.

Hannah McCarthy: But before we break, just your friendly weekly reminder that we have a newsletter and it's not one of those annoying things, we're not going to bombard you with emails. It's just the place where we put all of the fun [00:11:30] stuff that we learned about episodes while we were working on it. It is just a way to get to know us better and get to know more about civics. If you're into that, you can subscribe. Right now, it's at Civics101podcast.org. It comes out every other week and it's fun. All right.

Nick Capodice: Civics 101 is a listener supported show, support the show with whatever you can, depending on the price of gas right now at our website civics101podcast.org.

Hannah McCarthy: As [00:12:00] of this recording, January twenty fifth, 2022 gas in the U.S. is at an average of three dollars and twenty two cents a gallon, up from a dollar and 80 cents in spring of twenty twenty. So how Nick, do we get here so fast?

Nick Capodice: All right, here's Robert Rapier again.

Robert Rapier: Okay, so as the pandemic was starting to get heated up, Saudi Arabia and Russia decided to engage in a price war over [00:12:30] over oil that started prices dipping.

Nick Capodice: Hannah, something I didn't know about was the concept of futures and investing. Don't turn off the podcast. It's interesting, I promise. People invest in oil futures, which is a lot riskier than just buying stocks, because what you're doing is you're committing to owing an infinite amount of money. If you invest a thousand dollars in oil futures and the price goes way down. You don't just earn zero, you're on the hook [00:13:00] to owe a lot of money. Isn't that scary?

Hannah McCarthy: I don't know anything about investing. It's a good thing I don't do it.

Robert Rapier: And that's what happened, and a lot of people got caught. It caused some marginal producers to shut down. It caused some producers to go bankrupt. And then the pandemic hit and the stay at home orders and the demand for oil in the U.S. plummeted.

Hannah McCarthy: Oh, I remember this period, nobody was driving. We all had stay at home orders and so nobody was buying gas [00:13:30] and it was something like under $2 a gallon.

Nick Capodice: Yeah. And then slowly Americans started going back to work and back to school

Robert Rapier: After the stay at home order started to expire, demand started to recover and it recovered much faster than supply did. And so from negative prices, we saw prices start to take off. And then over the next year, supply was short. Demand increased back to about where it was and supply which had fallen by two [00:14:00] or three million barrels a day. It took a much longer time to come back online. If people say why and I said, well, some of the companies don't even exist anymore. Some of the marginal wells were shut in, and you can't bring those back online. If you've got a stripper well, producing a few barrels a day and suddenly prices are negative. You might permanently shut that well down and you're not going to bring it back online. And that is the primary reason oil prices skyrocketed and gasoline prices followed. That is the single biggest reason, much bigger factor than [00:14:30] anything Trump did or anything that Biden has done.

Hannah McCarthy: Ok, I'm ready for it. What can the president do to lower gas prices?

Nick Capodice: Alright, I got three for you. Three things. Here is Irina Ivanova again with number one.

Irina Ivanova: There's one specific thing that the president could do and that Biden actually has done. That has a little bit of an impact that it can create a little blip in gas prices. And that [00:15:00] is to release oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

Hannah McCarthy: What is the Strategic Petroleum Reserve? Just like a massive tank of gas somewhere?

Nick Capodice: Yeah, it's a system of caverns along the Gulf Coast, massive underground salt domes that are full of oil and that oil can be turned into gasoline. It was created in 1975 in response to the oil embargo, and it can hold seven hundred and fourteen million barrels of crude. Some caverns hold sweet crude, some caverns hold sour crude. I'm going [00:15:30] to get into that in the newsletter. But recently, Congress has been selling the oil in the reserve since 2015 to fund the deficit. And President Biden released 50 million barrels from it in November 2021.

Robert Rapier: Presidents frequently do it leading up to elections because high gas prices are not a prescription for getting, getting reelected. And so that's one. It's not a, I mean, you can't just keep doing that. We have a strategic petroleum reserve for a reason, so there is a risk in doing [00:16:00] it. But presidents have used that handle time and time again.

Irina Ivanova: And the main reason is really signaling right. And voters, voters love it, you know? So there is there is that effect of like, Oh, the president's looking out for me. In the grand scheme of things just to sort of put it into numbers, you know, we rereleased something like 50 million barrels of oil, that is roughly what the entire U.S. uses in a single day.

Hannah McCarthy: All [00:16:30] right, sounds like number one, tap the piggy bank. It's a gesture, but a relatively ineffective one, right? So what's number two?

Nick Capodice: Number two, it's to ban exports. Stop selling oil that we produce to other countries. Keep it all to ourselves, which we did for 40 years until 2015.

Robert Rapier: President Obama agreed to end that ban on oil exports, and what was happening at the time is fracking had had increased [00:17:00] oil supplie dramatically in the US.

Nick Capodice: Fracking by the way, or hydraulic fracturing is a method of extracting oil and natural gas from deep underground, and we were getting a lot more gas from fracking in 2015.

Robert Rapier: But there's a ban on exports, and so all of that had to go through domestic refineries. And that was depressing the price of oil. And what was happening is domestic refiners were then refining the oil, but there was no ban on finished product exports. [00:17:30] So finished product exports went through the roof. Refiners were printing money. And in reality, it didn't really affect gas prices because gas prices still were set by the global market. And so it just shifted who made who was making the money. So you could make an argument that maybe it might have some influence because it would depress oil prices in the US? But, you know, unless you're banning finished product exports to its just, refiners are going to make a lot more money. [00:18:00]

Hannah McCarthy: So Robert is saying that if we stop exporting, oil refineries will just export the gas and diesel they make from that oil, and nothing will change, except refiners make more money.

Nick Capodice: Yes. And there's another problem with stopping exports. Kind of an oil cold war.

Irina Ivanova: The bigger issue, which a lot of people brought up with this idea of banning oil exports, is that it would cause other oil producing countries to use a technical term to completely flip [00:18:30] out and lose their cool and and retaliate. I mean, if the U.S. can ban oil exports, other people can say, Well, we can't have your oil, you can't have our oil, you know, so, so so their their analysis is that it would just it would just lead to an arms race metaphorically where everybody's withholding their gasoline and we don't actually have, you know, more oil globally.

Nick Capodice: And [00:19:00] finally, action number three, cut taxes. There is a federal tax of about 18 cents per gallon of gasoline, but the much bigger tax comes from your state.

Irina Ivanova: Different states have very, very different amounts of taxes. There's Texas. Tennessee have very low fuel taxes. California famously has extremely high fuel taxes. On average, the tax that the [00:19:30] state imposes accounts for roughly 15 percent of the price at the pump. State governors could potentially try to make this stuff cheaper, and they, you know, they would work, especially in a place like California where you know, you're talking about 450 or more for for gas. You know, if, if, if you shave off 15 percent, that's that could be significant.

Hannah McCarthy: We're calling this episode the president and the price of gas, but [00:20:00] it sounds like you could just as easily call it the governor and the price of gas.

Nick Capodice: You could indeed, your state's own little president. Or maybe it'd be better to call the episode your state legislature and the price of gas, since they're the ones who actually write the laws.

Hannah McCarthy: Last thing I have heard a lot of criticism of President Biden's handling of the price of gasoline being tied to his decision to cancel the Keystone XL pipeline. Can we get into that?

Nick Capodice: Yeah.

Archival: Well, we have thousands of young people [00:20:30] here in the streets of Washington, D.C., marching to the White House to risk arrest, to demand the President Obama say no to Keystone XL...

Nick Capodice: So, briefly, the Keystone Pipeline project, it's a proposed pipeline that transported oil from Canada to Texas. It was the subject of years of protests by indigenous activists, landowners and environmental groups. It was a protest that spanned three presidential administrations, and it was a successful protest [00:21:00] as the project was abandoned in June 2021 after President Biden issued an executive order to ban the permit for it. Hannah, this is the talking point on conservative talk radio that the canceling of the pipeline increase the price of gas. So did it. Roberts says no.

Robert Rapier: Why wouldn't that influence oil prices? Because the Keystone pipeline, that supply wasn't going to come along for years, and we don't know what the demand situation is like [00:21:30] in years. So so this doesn't have a short term influence on oil prices. I said before, if scientists say we're going to have 50 percent more hurricanes in the Gulf Coast over the next two decades, that's not going to move oil prices. But if one is rolling through the Gulf Coast right now, it will. I mean, there's short term factors that increase the price, but longer term, these things just don't move the needle much. So a lot of the actions President Biden [00:22:00] has taken, although they can influence the price in the long run, people mistakenly assume that's why prices are moving now. And for a lot of people, I point out between the time of the election and the time Biden was sworn in, oil prices moved up 40 percent. Do you blame Trump for that?

Hannah McCarthy: Did people blame Trump for that?

Nick Capodice: House and Senate Democrats sure did. They blamed it on his recent sanctions of Iran. President Trump tweeted [00:22:30] at OPEC and said that they were to blame and they had to increase production. That didn't do much. So then he tweeted that it was Obama's fault because Obama had conspired with Saudi Arabia to lower prices before his reelection. Anyways, this is a playbook both parties have used. But to reiterate the effect of the Keystone Pipeline project, Irina spoke to Tom Kloza from OPIS, which is a major market analysis firm. And Tom said "The Keystone decision is something [00:23:00] that might come back and haunt the administration in 2023. But it has absolutely nothing to do with why crude oil prices now have rallied so much since April 2020."

Hannah McCarthy: Okay, this is making me think about the fact that no matter how much power we perceive our chief executive as having, sometimes we lose sight of the fact that there are instances where they are not the most important person in the room. And when I look at how the price of gas here tracks exactly with oil prices [00:23:30] globally, it's also clear that just like a lot of issues when it comes to the price of oil, the United States is not the most important person in the room, either.

Nick Capodice: We should make a new sticker.

Hannah McCarthy: Oh, yeah, what should we put on it?

Nick Capodice: It like a huge sticker that is an illustrated embodiment of the global crude oil market saying, I did that! And then like much smaller, a sticker that's got like the House and the Senate. And like 50 different state legislatures and all the governors, [00:24:00] the department who runs the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and you've got to like, have Nixon and Carter on it too, maybe actually every president thus far sort of all holding hands like it's a small world and they're all singing "and we all kind of helped."

Hannah McCarthy: I'll call the print shop.

Nick Capodice: Well, that'll just about do it. Today's episode was produced by me Nick Capodice with Hannah McCarthy. Our staff includes Christina Phillips and Jcqui Fulton. Rebecca Lavoie is our executive producer and doesn't [00:24:30] need to heat her home because of her coat. Because of her amazing jacket. Music In this episode by the inimitable Chris Zabriskie, Kevin McCleod, Lobo Loco, Dyalla, broke for free, Nico Staf, Bobby Renz, and this track playing here. We love it so much. Whispering through by Asura. Civics 101 is a production of NHPR, New Hampshire Public Radio.