In this episode of our Starter Kit series, we explore the powers of the President, both constitutional and extra-constitutional. What can a president do? How long do a president’s actions reverberate? Why don’t we do treaties anymore?

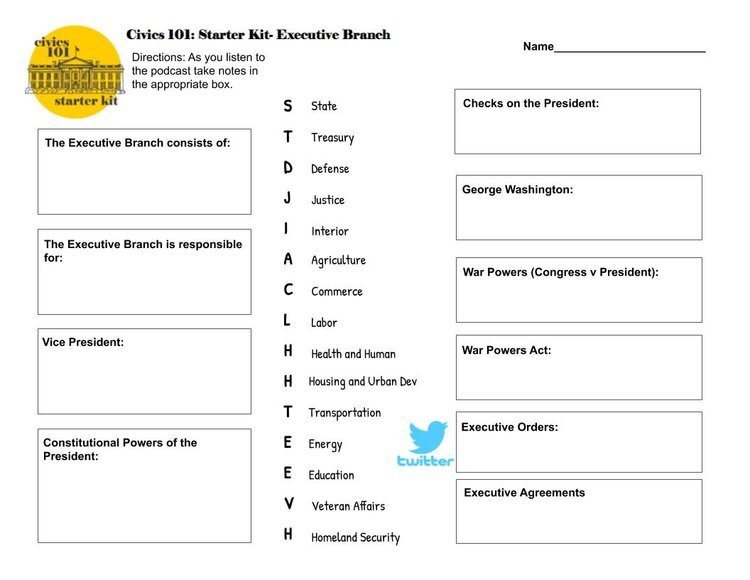

Also, we’ve got a super inefficient mnemonic device to remember the 15 executive departments in the order of their creation.

Featuring the voices of Lisa Manheim, professor at UW School of Law and co-author of The Limits of Presidential Power, and Kathryn DePalo, professor at Florida International University and past president of the Florida Political Science Association.

Episode segments

TRANSCRIPT

NOTE: This transcript was generated using an automated transcription service, and may contain typographical errors.

Starter Kit: Executive Branch

[00:00:04] (Presidential Oath of Office)

[00:00:26] Congratulations Mr. President.

[00:00:43] I've got a pen to take executive actions where Congress won't.

[00:00:46] I'm announcing my choice today, and will submit Judge Stevens name formally.

[00:00:51] What I'm going to do when I veto this is to say yes I'm going to send this bill right back.

[00:00:55] I'm signing today an executive order establishing the President's Task Force on Victims of Crime

Nick Capodice: [00:01:05] Ring a ding ding. What if the president picks up.

[00:01:09] Please continue to hold.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:01:14] What on earth is that.

Nick Capodice: [00:01:15] I called the president to make a comment. And I was on hold for about 20 minutes.

Nick Capodice: [00:01:23] Starts off the same way. Much like presidencies. Got hope at first. Comes along with a little trouble along the way. But the next thing you know. A Volunteer will answer. And take my comment to the president.

[00:01:51] Comment Line volunteer operators are currently assisting other callers.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:01:55] Did a volunteer actually end up talking to you.

Nick Capodice: [00:01:58] Yes one did and she told me that my comments would be delivered to the West Wing. Because no office is untouchable by the American citizen. I hope.

Nick Capodice: [00:02:09] I'm not Captain E.J.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:02:11] I'm Hannah McCarthy.

Nick Capodice: [00:02:12] And this is Civics 101, our starter kit series, and today we are tackling the most powerful job in the world. Or, as President James K. Polk put it, no bed of roses. We're talking about the Executive Branch.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:02:26] It's one of my favorite questions that the listener submitted. "What does the president do?"

Nick Capodice: [00:02:32] So when I think of the Executive branch, of course the first thing I think about is the president. But there is so much more. I spoke with Lisa Manheim. She's a lawyer and professor at University of Washington School of Law and co-author of The Limits of Presidential Power.

Lisa Manheim: [00:02:47] The executive branch has about has several million people working in it and there are about 2 million people who work as civilians within the executive branch. And then there are about 2 million people who work in the military.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:03:00] Over 4 million.

Nick Capodice: [00:03:02] Yeah. And the president is at the very top. The Constitution gives the president the power to execute the laws.

Lisa Manheim: [00:03:10] And one way of understanding what that is is it is the power to take the laws that Congress has passed, and they might relate to food safety or education or national security, and those laws need to be executed. They need to be carried out and enforced. And so the president via the constitution has the power to execute those laws. And what that refers to in practice is really helping to oversee a an executive branch that consists of literally millions of people who are doing the work of carrying out those laws passed by Congress.

Nick Capodice: [00:03:45] So this includes federal law enforcement. This is like the FBI and the Department of Justice employees, but also every member of the civil service. This is every post office worker, every national park employee. By contrast the legislative and judicial branches each have about 30000. The Executive branch is the single largest employer in the world. Twice as many employees as Wal-Mart. There are hundreds of agencies that fall within the 15 departments of the executive branch. All 15 of these departments can should and will get their own episode. But just so you know them all, you know I'm a sucker for a good mnemonic right Hannah?

Hannah McCarthy: [00:04:22] I do.

Nick Capodice: [00:04:23] Here's a super impractical one that I adore. See that dog jump in a circle. Leave her house to entertain educated veterans homes.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:04:31] See that dog jump in a circle. Leave her house to entertain educated veterans homes.

[00:04:37] Now you're on the trolley. STDJIACLEHTEEVH, fifteen federal departments in the order of their creation. S state department, handling our relationship with foreign countries. T. Treasury. They make the money they collect taxes they include the IRS D defense. That's our largest department. J. Justice. They enforce the laws that protect public safety. This includes the FBI and U.S. Marshals. I, interior, manages the conservation of our land. This includes the National Parks, A Agriculture USDA they oversee farming food. C, commerce. They promote our economy and handle international trade. L labor, our workforce. H, Health and Human Services. That includes the FDA and the CDC. They also manage medicare and medicaid. H, Housing and Urban Development, HUD. They address national housing needs. T, Transportation. That's federal highways and the Federal Aviation Administration. E energy, the DOE, they manage our energy and they research better ways to make it. The next E's education. You know what they do. V, veterans affairs, benefit programs for those who've served in the military, and finally Homeland Security, whose job is to prevent and disrupt terrorist attacks within the United States.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:05:43] Right. Homeland Security. That's the newest one. It was just after September 11th.

Nick Capodice: [00:05:47] And the president hires, with the Senate's approval, and fires, without necessarily, political appointees to these departments.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:05:55] Wait before you jump into the president. I think that you are missing something.

Nick Capodice: [00:06:00] What? Oh. The vice president.

Nick Capodice: [00:06:10] All right. To be fair it's easy to overlook the vice president because the job just doesn't come with a lot of official duties. The veep is next in succession in case anything happens to the president, a heartbeat away from the Oval Office. They also serve as president of the Senate. Breaking tie votes when necessary. And that's happened about 270 times. And they preside over nonpresidential impeachment trials. Interestingly when it's a presidential impeachment it's the chief justice of the Supreme Court that runs the trial. Can you imagine that. And then over the last century the role the vice president has shifted a bit more towards domestic and foreign policy and sort of less sitting in that seat in the Senate as the president.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:06:52] Ok. Thank you. So we've talked about the millions in the executive branch but what does the president do?

Nick Capodice: [00:06:59] OK. There are constitutional powers of the president as well as more political powers. So let's start with what's written on the parchment. Here is Lisa Manheim again.

Lisa Manheim: [00:07:10] The Constitution creates the office of the president but it's sort of surprisingly has relatively little to say in the actual text about the range of different powers that a president in particular President these days has and is able to execute. That being said there are, the Constitution does include a relatively short list of specific powers that it grants the president and three of the most important relate to laws that Congress pass, who's appointed in the federal government, and then finally issues that relate to foreign affairs or to the military.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:07:45] The first of those three powers is signing bills into law or vetoing them.

Nick Capodice: [00:07:50] Which Congress can override with a two thirds majority in both houses.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:07:53] The second is appointing people to powerful positions in those 15 departments.

Nick Capodice: [00:07:58] Including Supreme Court justices. There are about 4000 positions that the president appoints. Twelve hundred of which require Senate approval.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:08:06] Ok. And the third the Foreign Affairs and the military that's forming treaties with other nations and being commander in chief of the armed forces.

Nick Capodice: [00:08:14] Right. And there's one more constitutional power that the president "shall from time to time give the Congress Information of the state of the Union," which they used to call the Annual Address and it used to be a written administrative report on what all the many executive employees had been up to. But radio and television have altered it to the State of the Union that we know and love today.

[00:08:34] Mr. Speaker. the president. of the United States.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:08:39] I've always thought that when you look at it on the page right there in Article 2 of the Constitution, for a job that's called one of the most powerful in the world, there aren't that many powers and they're all checked. The president appoints nominees but the Senate approves them. The president can create or sign treaties but two thirds of the Senate has to concur. Did the founders intentionally make it a not very powerful position?

Nick Capodice: [00:09:07] Well let's duck into that hot room in Philadelphia at the Constitutional convention. Because they all knew they wanted an executive branch, which the articles of confederation did not have. And they were like, We want someone like the guy running these proceedings, someone who can also lead the troops into battle. Like General George Washington. Like that guy.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:09:27] So they picked the candidate and then they wrote the job description.

Nick Capodice: [00:09:31] Yes. And that's one reason for our unique way that the branches divvy up war powers.

Kathryn DePalo: [00:09:36] The Constitution if you want to talk about separation of powers checks and balances there you know has given Congress so the people's branch right in the people's house the ability to declare a war.

Nick Capodice: [00:09:47] This is Kathryn DePalo, she's a political science professor at Florida International University.

Kathryn DePalo: [00:09:52] And that is very specific language but also gave the president of the United States the power as commander in chief. And so once Congress declared the war, the president then was supposed to lead the troops if you will. But that really hasn't happened at all. I mean the last time we declared war was in World War 2.

Nick Capodice: [00:10:09] There has been a consistent give and take between the legislative and executive branches when it comes to war.

Kathryn DePalo: [00:10:15] One of the things I find actually fascinating is the War Powers Resolution or the War Powers Act of 1973. And that was sort of the height of Vietnam. Everyone hated this war including members of Congress.

[00:10:34] Under the Constitution, you can end the war, not another dime for this war!

Kathryn DePalo: [00:10:41] And so what they wanted to do was try to take power away from the presidency. And so they passed this law that basically says the president cannot unilaterally send troops wherever he wants to. Just because he's commander in chief that you know the president has to inform Congress within 48 hours Congress, within a 60 day period has to decide if they want to continue with this war and continue to fund this this particular war. But a lot of wars aside from some of our recent war certainly in Afghanistan and Iraq really wrapped up very quickly. You know we didn't declare war you know when we went into Iraq the first time. And so the president really has a lot of the ability to send the troops and then say to Congress, oh well what are you going to do now. Right? These troops are here. So there's a lot of these things that are extra constitutional that would suggest there's a strict separation of powers here but really especially with the president of the United States and reality can do a lot.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:11:35] It sounds like we are getting into the territory of executive branch loopholes.

Nick Capodice: [00:11:41] Did you ever see these Saturday Night Live parody of the I'm just a bill song from Schoolhouse Rock with the executive order?

Hannah McCarthy: [00:11:45] No!

[00:11:49] I'm an executive order and I pretty much just happen.

Kathryn DePalo: [00:11:56] Well I think human nature is we always seek out those loopholes. Right. So so of course there there are certainly loopholes and you know to talk about the presidency certainly to go around Congress. You know especially if the president's having difficulty getting Congress passed desired legislation the president as the chief executive of the executive bureaucracy can issue executive orders and basically make a whole lot of changes. You know President Obama couldn't get some immigration policy passed through Congress so he signs executive orders like the DREAM Act which which kept a lot of these kids who had graduated from American high schools to be able to stay here. And that's an order really to get to the the executive branch and to ICE. And so you can essentially make a lot of policy in those particular ways to be official.

Nick Capodice: [00:12:45] Executive orders need to be signed and recorded in the Federal Register and each of them gets an official number. I love executive orders they're fascinating. And every single president has issued them with the solitary exception of William Henry Harrison.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:12:57] To be fair he did die 31 days into office he probably would have done a few.

Nick Capodice: [00:13:02] We don't know that, we'll never know for sure. George Washington, he did eight. Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863 was technically an executive order. The record for those so far is FDR Franklin Delano Roosevelt three thousand five hundred twenty two executive orders, one of those was executive order 7 0 3 4 which created the Works Progress Administration, one of the primary ways FDR sought to combat the Great Depression. But as of very recently, determining what is an executive order has become a bit muddy.

Lisa Manheim: [00:13:35] When President Trump publishes a tweet, there is an argument that that is itself an executive order. It's not a formal executive order. It's not being published in the Federal Register. But legally speaking if the president issues a clear direction and does so in the form of a tweet that has the same legal effect as a formal executive order that's published in the Federal Register.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:13:59] So executive orders are just the president telling the people of the United States and all three branches of government their instructions.

Nick Capodice: [00:14:08] Yes. And these executive orders can still be blocked by the Supreme Court or by Congress if they pass a bill invalidating the order. And executive orders are different from executive agreements. Those are agreements that the president enters into with a foreign country.

Lisa Manheim: [00:14:23] And so if a question is Well why would a President ever enter into an executive agreement which he can do on his own rather than deciding to involve the Senate and enter into a treaty. There are basically two answers. One is that actually Presidents very rarely do enter into treaties now in part because they take this other route of entering into executive agreement. The other answer is that if a president enters into executive agreement rather than into a treaty then it's much easier for the next president if he wants to to exit the executive agreement than it is to executive exit a treaty. And that's one of the reasons why President Trump was able to start the unwinding process for the Paris agreement about climate change even though President Obama had just entered into it.

Nick Capodice: [00:15:13] George W. Bush he submitted about 100 treaties during his administration and most of them were approved by the Senate. And that's been pretty much the average since the beginning. By contrast Obama submitted 38. Only 15 of which were approved. However executive agreements which require no other branch involvement they are on the rise and American presidents have issued about 18000 of those.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:15:38] I'm curious as to the limits of these executive orders and agreements. Can a president order anything they want.

Lisa Manheim: [00:15:49] The fundamental principle that's underlying all this is the idea that if the president takes an official action there has to be some legal source of authority and the legal source of authority has to come from either a law passed by Congress or from the Constitution itself. The executive agreement is the tool the executive order is the tool and it's something in a Congress in one of Congress's laws or in the Courts Union itself that provides the basis for the president using that tool.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:16:20] One last thing I've got to know about. How persistent are the effects of precedent because if you love a president's agenda you might want them to issue as many orders and agreements as possible. Or if you loathe an administration you want to elect someone who will throw everything out and start anew. How long do a president's actions reverberate.

Nick Capodice: [00:16:44] That is an excellent question.

Lisa Manheim: [00:16:46] Legally speaking one way of understanding how permanent a president's actions are is to think about the process the president used to take those actions because for the most part the harder it is in terms of the process for a president is to take an action the harder it is in the future going to be for a president to unwind that same action. So for example if the president is, were to sign a bill into law, that means that two houses of Congress came together and agreed on the same statutory language which they then present to the president and the president signs it into law. For the next president to make that law go away? The president on his own cannot eliminate that prior law. By contrast if the president takes some sort of action all on his own. So if the president decides I'm going to issue an executive order directing people in my own administration to try to adopt certain enforcement priorities when it comes to immigration or if the president says I'm going to enter into an agreement with a foreign country and I'm not going to involve the Senate, I'm not gonna involve Congress at all I'm just going to sign it on my own. If the president does something on his own then generally speaking as a legal matter the next president can come in and unwind that on his own.

Nick Capodice: [00:18:07] There are different ways you can be a president you can be a military figurehead like George Washington who didn't necessarily even want the job, or you can be like Eisenhower or Kennedy you work like crazy to broker deals with the House and Senate getting a ton of laws passed and treaties signed or you can say forget that I'm gonna just go it alone and use those presidential powers. But again Congress can pass legislation to overturn an executive order and the courts can deem them unconstitutional. For example Donald Trump's travel ban was an executive order that a judge ruled against the law and no individual action on the part of the president could change that.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:18:47] Until he wrote another executive order which the Supreme Court upheld.

Nick Capodice: [00:18:55] Yeah. There's sort of one last vestige of the power of the president that Lisa told me about. And the thing is it depends on how powerful we let the president be.

Lisa Manheim: [00:19:05] Given the role that the president plays as in a sense the single person that the news can go to that people can look to that foreign countries can can refer to. In thinking about what the United States government means and what it's doing in light of that position that the president plays. The president has over time gained an enormous amount of in a sense political power.

Nick Capodice: [00:19:33] And this didn't happen overnight. Administration to administration presidents have set precedent that gives the office more power. And we have no idea how that will evolve in the next 250 years. But I will say presidents often add tools to their executive toolbox but very rarely take them out.

Nick Capodice: [00:19:59] Well that'll just about do it for today's episode in the executive branch. Today's episode was produced by me Nick Capodice with you Hannah McCarthy thank you.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:20:06] Our staff. You're welcome. Our staff includes Jackie Helbert and Ben Henry.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:20:10] Erika Janik is our executive producer which means she executes the episode and Maureen MacMurray, whose job description was written after she was hired.

Nick Capodice: [00:20:18] Music In this episode is by supercontinent, pictures of a floating world, Bisou, Daniel Birch, Chris Zabriskie, Ask Again, Asura, and the United States Coast Guard band. This here is Tone Ranger.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:20:28] Civics 101 is made possible in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and is a production of NHPR, New Hampshire Public Radio.

Nick Capodice: [00:20:36] And don't you forget you too can call the president to make a comment. 2 0 2 4 5 6 1 1 1 1.