The terrorist attacks on September 11th, 2001, made one thing very obvious: our country’s national security strategy was flawed. What followed was one of the biggest reorganizations of our federal government in history: the creation of the Department of Homeland Security in November, 2002.

What about 9/11, the attacks, and their aftermath, made it possible for the government to transform, in just over a year? And how has that transformation changed how our government makes decisions about threats to our country, and responds to them?

Helping us untangle this story are: David Schanzer, the director of the Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security at Duke University; Darren Davis, a politics professor at the University of Notre Dame who studies public opinion and political behavior; and Eileen Sullivan, the Homeland Security Correspondent for the New York Times.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this episode misstated that prior to 9/11, a person applied for a visa through the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

Click here for a Graphic Organizer for students to fill out while listening to the episode

Episode Resources

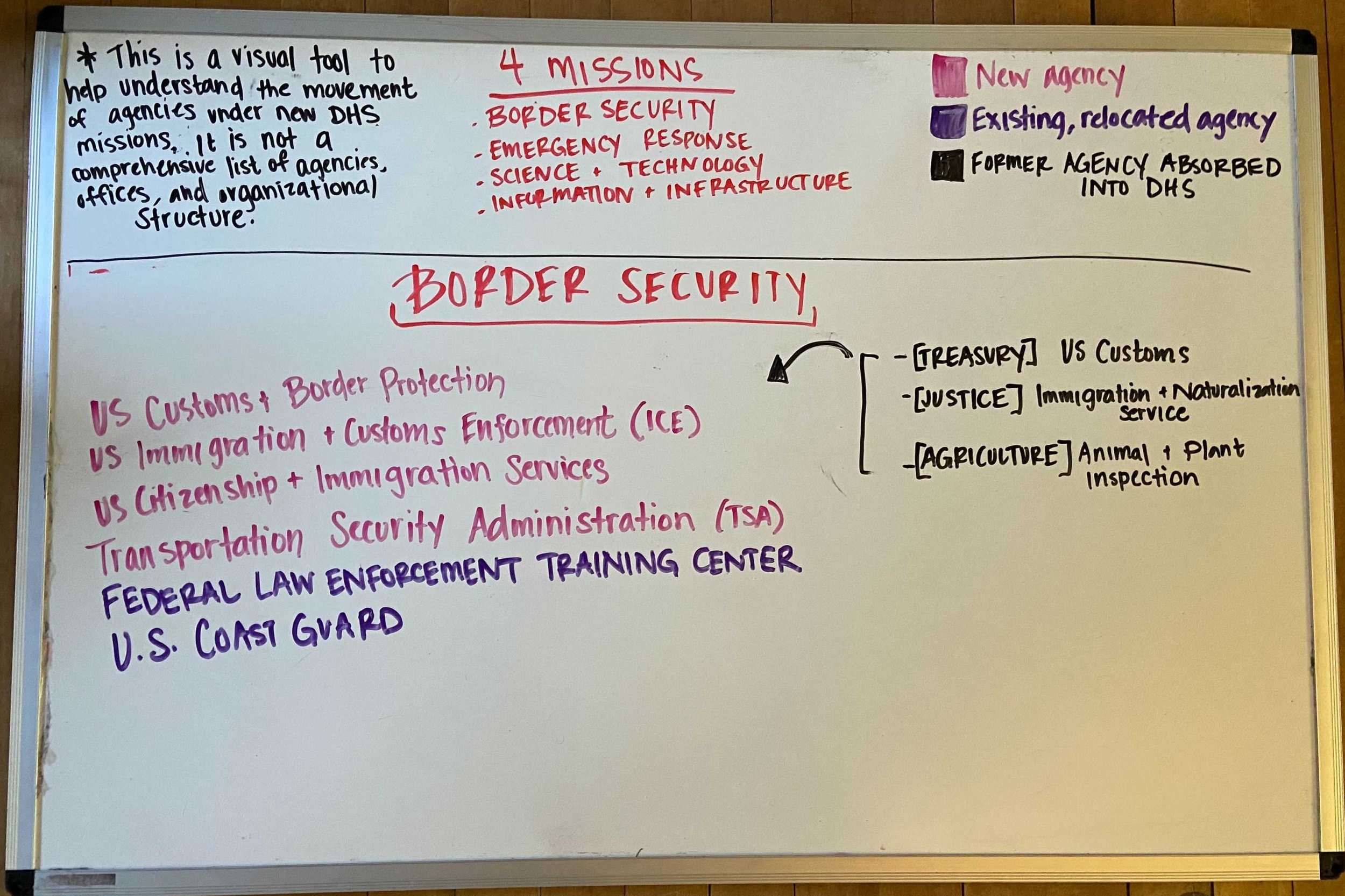

Christina’s attempt to organize the Department of Homeland Security by mission. To find DHS’s complete organizational chart, click here.

Episode Segments

Transcript

DHS final.mp3

Christina Phillips: [00:00:03] I have hit record! We are going.

Nick Capodice: [00:00:09] Well, let me start by saying it is lovely to see you in this chair, Christina.

Christina Phillips: [00:00:13] It is so wonderful to be here in the studio with you, face to face.

Nick Capodice: [00:00:17] Everyone. This is Christina Phillips. She is our senior producer, and she's going to be stepping in for Hannah this week. She is about to take us on a journey and she has been, quite frankly, busy.

Christina Phillips: [00:00:28] Yeah, so I thought I'd given myself a pretty straightforward task, which was explaining how September eleventh led to the creation of the Department of Homeland Security and why that matters.

Nick Capodice: [00:00:40] And this is the executive department that combined twenty two agencies from several different departments under one roof, right?

Christina Phillips: [00:00:47] Yeah. And created a few new agencies on top of that, all for the purpose of preparing for preventing and responding to domestic emergencies, especially terrorism. And let me tell you, just trying to figure out what moved where and why was a pretty enormous task. I ended up mapping it out on a whiteboard that is the size of a window. Wow. Imagine what it was like for the federal government to decide to do this in the first place, upend dozens of agencies and more than one hundred and sixty nine thousand employees, and fold them into a brand new department that has one mission to protect the homeland.

Nick Capodice: [00:01:22] Now this need to protect the homeland that didn't exist before 9/11.

Christina Phillips: [00:01:27] Well, our government has always had the role of providing for the common defense since the founding of our nation. It's in our constitution, right? But it took one day, one series of attacks for the government to be able to completely reshape what that means over an extremely compressed timeline. You'd think that something as serious as national security would still be subject to the slow grind of democracy that our government love so much. But it only took 14 months for Congress to pass the Homeland Security Act on November 25th, 2002 and establish a brand new executive department

Nick Capodice: [00:02:01] A very short time.

Christina Phillips: [00:02:03] And what I'm so interested in is what was it about that day, about that moment that made it so urgent, so possible for the government to start looking at itself differently enough so that it could create a new department? And once we've created this thing, what does that actually look like? Before we can talk about what the Department of Homeland Security is and does, we've got to take a step back and talk about how we got there.

Nick Capodice: [00:02:29] All right, let's get into it.

Christina Phillips: [00:02:34] Five strangers come into contact with the federal government. At the same time, a woman arrives at the Mexico side of the U.S.-Mexico border with a temporary work visa.

Archival Audio: [00:02:43] "The National Weather Service has issued a tornado warning."

Christina Phillips: [00:02:46] An emergency services dispatcher in Missouri issues a tornado warning.

Christina Phillips: [00:02:51] The captain of a shipping vessel from England sails into a port in Newark, New Jersey. The vice president climbs into a car that takes her to a speaking engagement near the U.S. Capitol.

Archival Audio: [00:03:03] "This is a final boarding call for the..."

Christina Phillips: [00:03:04] A man arrives at an airport in New York City to board a flight.

Christina Phillips: [00:03:09] What each of these people have in common is that they are face to face with the Department of Homeland Security, but their experiences would have been very different if they happened prior to 9/11. Before the terrorist group Al-Qaida hijacked four planes and killed nearly 3000 civilians in an attack on U.S. soil.

Archival Audio: [00:03:25] Eyewitness News. The unthinkable happened today the World Trade Center.

Archival Audio: [00:03:29] Both towers gone and we are all and we're just beginning to understand the extent of the catastrophe.

President Bush: [00:03:36] Tonight is the most extensive reorganization of the federal government since the 1940s. During his presidency, Harry Truman recognized that our nation...

Christina Phillips: [00:03:47] This is the story of how the government transformed itself after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, by creating a new executive department designed specifically to prevent and respond to threats. So Nick, what do you remember about the creation of the Department of Homeland Security?

Nick Capodice: [00:04:07] I remember it was swift and massive.

Christina Phillips: [00:04:10] Yeah, this was the biggest reorganization of the federal government since 1947, which, by the way, that reorganization was also because of national security. It was called the National Security Act of 1947, and it moved military operations like the Army, Navy and Air Force under a Department of Defense and created the CIA and the National Security Council.

Nick Capodice: [00:04:31] And this was after World War Two with a brewing Cold War on the horizon. But September 11th was not a war. It was an attack, and it took place on a single day.

Christina Phillips: [00:04:43] I asked David Schanzer, who's the director of the Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security at Duke University, to walk me through the aspects of the 9/11 terrorist attacks that felt different from anything the government had responded to before.

David Schanzer: [00:04:56] The attacks demonstrated multiple vulnerabilities and multiple, you know, gaps and things that went wrong during the day.

Christina Phillips: [00:05:06] David was a staffer for the U.S. Senate on 9/11, and he was there for the creation of the Department of Homeland Security. He talks about some of the systems that were exploited by Al Qaida.

David Schanzer: [00:05:15] All the hijackers were able to enter the United States. Their applications were generally fraudulent, but they entered. They got visas to come into the US.

Christina Phillips: [00:05:26] I just want to pause because that's three different departments right there. Before 9/11, a person applied for a visa through the State Department, and before entering the U.S. their visa was screened by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, which was in the Justice Department. And then their property was examined by U.S. customs, which was in the Treasury Department.

Nick Capodice: [00:05:45] I think I'm starting to see where you're going here.

David Schanzer: [00:05:48] Our aviation system, of course, was shown to be extremely vulnerable that they could bring knives on planes. And we know nothing about people as they were boarding.

Nick Capodice: [00:05:59] And that's airport security, which used to be just private security agencies. When I was a kid, there was a metal detector, but that was about it. You didn't even need an I.D. to get on a plane back then. You could just walk up to the gate.

Christina Phillips: [00:06:11] Well before 9/11, there was something called the computer assisted passenger prescreening system, or CAPPS, which was shared between the Federal Aviation Administration and the FBI. It was created in the 1990s because of concerns about terrorism, so certain passengers would have their checked baggage screened for explosives. But you're right, there was minimal security screening for most passengers, and airlines had to hire their own security. The Transportation Security Administration did not exist.

David Schanzer: [00:06:40] They were shown to be a lack of real coordination between the different law enforcement and intelligence entities. The CIA knew that al Qaeda was planning some sort of spectacular attack. They didn't know where or when. Of course, a lot of that information didn't get passed on to the FBI. The FBI was tracking some people. Then they lost track of them.

Christina Phillips: [00:07:02] By the way, we covered this in more depth in our episode about the FBI. So check that out. The point is, the style of terrorist attacks planned by Al Qaida revealed just how vulnerable our country was and that the existing approach to national security wasn't sufficient and that there were some security measures that didn't exist at all.

David Schanzer: [00:07:21] So all of these issues led to this movement to create many different reforms. The most comprehensive one was to create a Department of Homeland Security that was placing all the different agencies with responsibility for the protection. The regulation, essentially the creation of borders, whether they be borders by air, by sea, by land, all into one department.

Nick Capodice: [00:07:46] But terrorism wasn't unheard of in the United States until September 11th. And it wasn't even the first terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. I remember in 1993, a terrorist detonated a bomb in a truck in the parking garage below the North Tower.

Christina Phillips: [00:08:01] That's what I think is key here. The federal government had been thinking about new threats to national security, but politicians were also thinking about everything else the economy, health care, education. There had actually been a study in 1998 called the Commission on National Security in the 21st Century that was quote "the most comprehensive review of American security since the National Security Act of 1947"

Nick Capodice: [00:08:24] Which, as you said earlier, was the last time the government had undergone a major reorganization.

Christina Phillips: [00:08:29] The study was more commonly known as the Hart Rudman Commission after lead author Gary Hart and Warren Rudman. They said that a lack of coordination across agencies in the circumstances of a terrorist attack or disaster was a huge concern. In fact, Warren Rudman, a former Republican senator from New Hampshire, talked about this exact problem in February 2001 on C-SPAN

Nick Capodice: [00:08:53] February, seven months before nine eleven.

Warren Rudman: [00:08:57] Yes, the responsibility for dealing with that kind of a disaster in this country currently is spread across 46 federal agencies, which do not have good coordination with each other. We believe that this is such a serious threat that we're not talking about creating a new bureaucracy. We're talking about probably reducing the bureaucracy by moving the functions and these units into a Homeland Security Agency, which will then be.

Nick Capodice: [00:09:25] Oh, interesting. So that term Homeland Security was being tossed around in government circles before September 11.

Christina Phillips: [00:09:32] Yeah, the term is not new. But before the September 11th attacks, the discussions around protecting the homeland were much more theoretical. I watched some of the congressional hearings about the Hart Rudman Commission, and the politicians were talking a lot about budgeting and turf. You know who's going to do what? Who is going to pay for it? What are we going to give up in order to do it? And what makes that national security threat go from something theoretical into an actual plan? And action has to do with the experience of the attacks for the public. The September 11th attacks felt new.

Darren Davis: [00:10:04] The crucial difference for nine 11 for the average American citizen was that there were innocent victims.

Christina Phillips: [00:10:11] This is Darren Davis. He's a professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame. He actually surveyed Americans right after 9-11 and asked how they were feeling in that moment about terrorist attacks and their government.

Darren Davis: [00:10:24] In the immediate aftermath. Many American citizens were thinking that there were more terrorist attacks to follow. So there's this belief that they needed to be protected.

Christina Phillips: [00:10:35] Darren talks about this trade off that people have to make between being protected from terrorism and being protected from the government's encroachment on our civil liberties.

Darren Davis: [00:10:44] When the government is attacked, when American citizens are attacked, when they've been attacked in the past. American citizens can be expected to give up their rights. Congress can be expected to concede to a more powerful president for fear of being considered unpatriotic.

Christina Phillips: [00:11:03] The media also played a role in this.

Darren Davis: [00:11:05] The media acquiescence to a more powerful president for fear of being considered unpatriotic.

Nick Capodice: [00:11:15] The coverage was relentless. There was nothing else being talked about on radio or TV or in newspapers for months, like my friend and I used to say, walking around whatever we'd see the sign that said, never forget. We're like, I don't think that's very likely. I don't think anybody's going to be forgetting this anytime soon.

Christina Phillips: [00:11:33] The media does set a tone and for example, in World War Two, when media was reporting on what was happening during the war, there were choices made like suppressing information until after an attack happened for the greater purpose of success in the war.

Nick Capodice: [00:11:49] So it's yeah, it's just so interesting in such a tenuous line, right? I'm keeping you misinformed for your safety and for the country's safety. It always leads to an ultimate question is this a good thing or not? So was that happening in the aftermath of the attacks on 9-11?

Christina Phillips: [00:12:04] Well, after 9-11, there was a lot of coverage of how the government was acting to keep people safe. There was a lot of opportunity for politicians to talk to the people. I mean, they were on the news all the time. And so there was a lot of access to the government and the government was getting a lot of access to the public through the media. Which brings me to the last big factor that made this massive reorganization possible. 9-11 had a uniting effect on the country.

Darren Davis: [00:12:29] Normally, the two political parties are deliberative. But one of the things I want to point out is that this came months after the 2000 election between Bush and Gore, and the government was extremely divided because that election had to be decided by the Supreme Court

Christina Phillips: [00:12:52] Because the decision is being taken out of the hands of the people and put into the hands of the Supreme Court. It just draws out this political tension. It was a really divisive moment, especially when it came to trusting that democratic process in supporting the incoming president

Darren Davis: [00:13:08] And politicians, and the public began to rally as expected behind George Bush.

Christina Phillips: [00:13:16] After nine 11, President Bush's approval rating rose from around 60 percent to 92 percent, including 88 percent of Democrats. This was one of the highest approval ratings for a president ever.

Nick Capodice: [00:13:28] To add to that, presidents and congresses are more effective when they have high approval ratings. They can get more done.

Darren Davis: [00:13:36] So here's the irony of all of this is that over time, as the government began to use. Its ability to protect its citizens, it began to lose support when the government began to lose support and trust declined, people were unwilling at that point to concede their civil liberties. So the immediate context of 911 is really, really important. What happened over time is also important because it shows that without trust, government can't do very much.

Nick Capodice: [00:14:12] We're going to keep exploring this new umbrella department, but first we're going to take a quick break. But before we do, if anyone is interested in all the ephemera, trivia and stuff that gets left on the cutting room floor of our episodes, Hannah and I write a biweekly newsletter called Extra Credit. It's free, and you can sign up at our website, civics101podcast.org.

Christina Phillips: [00:14:38] Civics 101 is produced by a nonprofit journalism outlet, New Hampshire Public Radio. We can only do what we do because listeners just like you chip in a few bucks, sometimes more than a few, to support our work. If you'd like to donate to the cause. Head over to Civics101podcast.org or click the link in the show notes.

Nick Capodice: [00:14:57] All right, so you've got this massive pressure from the American people to focus on terrorism. What were the first steps towards this massive consolidation to address that?

Christina Phillips: [00:15:07] The first thing President Bush did was issue an executive order creating a new Office of Homeland Security on September 20th, 2001. So this is not a department. President Bush said that this office and the director he appointed would develop a national strategy of Homeland Security and coordinate efforts across other departments.

Nick Capodice: [00:15:28] Had they plan to create this department by this time?

Christina Phillips: [00:15:30] No, no. So at this point, it's really like President Bush recognized that there's a whole bunch of agencies that are responding to terrorism, and he says, OK, I'm going to put this one guy in charge of helping communicate and organize all of these departments and agencies that are all trying to respond to terrorism in different ways.

Nick Capodice: [00:15:48] He's going to figure out a way to get them to, like, talk to each other.

Christina Phillips: [00:15:51] Yes, and and set a plan for how they'll respond in the future.

Nick Capodice: [00:15:56] So tell me about the guy they decided to put in charge.

Christina Phillips: [00:15:59] That would be Tom Ridge. He is the governor of Pennsylvania, and he started on October 8th, 2001.

Nick Capodice: [00:16:06] And what was Tom Ridge actually able to do? Could he give orders to the FBI, to the DOJ Department of Transportation just to make sure they're all now focused on this new Homeland Security strategy?

Christina Phillips: [00:16:19] So you're not the only person to ask that question.

Archival Audio: [00:16:23] If there's a bioterrorist, a large scale bioterrorist act in the future, who is in charge of the response, who has authority to make decisions related to the response, but I'm trying to find out basically is are you the boss here or are you a coordinator?

Tom Ridge: [00:16:37] If there is A well, I guess, you know, the coordinator, it's like a conductor with an orchestra. The music doesn't start playing until he taps the baton.

Christina Phillips: [00:16:47] That was a reporter at a press conference 10 days after Ridge started his official duties as director. It was in the middle of this other big attack that happened after 911, when someone mailed anthrax spores to congressional delegates and news agencies from a New Jersey post office, which ended up killing five people.

Archival Audio: [00:17:03] In just a week's time, we have had four confirmed cases of anthrax, all with media connections and a number of anthrax scares as well.

Christina Phillips: [00:17:10] In this press conference to explain how the government was responding to the anthrax attack and explaining his role as this new director of Homeland Security Tom Ridge was on stage with the head of the FBI leaders from the Department of Health and Human Services, the postmaster general, and several other people who were all responding to the anthrax attack. Ok, I promise this is related, but when I trained to be a wilderness EMT,

Nick Capodice: [00:17:33] You were a wilderness EMT.

Christina Phillips: [00:17:35] Yes, I was. It was mostly for my own safety, especially when I went on hikes. I'm very accident prone. But anyway, one thing you learn in search and rescue situations where you actually need to go out and find someone and provide medical attention in the wilderness like an injured hiker is that there needs to be an obvious hierarchy and there are people who understand what their role is. The person carrying the water, the person following the map, the person monitoring the patient, everyone there knows what they're doing and what everyone else is doing. And you've all agreed ahead of time on how it will work. And there's one person who's in charge of the whole thing, which is ideally how things could have worked with Tom Ridge in this new Office of Homeland Security.

Nick Capodice: [00:18:13] The difference here between the government and a hiker is that this is a federal emergency, but the government is still running at the same time.

Christina Phillips: [00:18:21] Yeah, and they're not used to responding to attacks like these in a coordinated way. They're writing the manual as they go and the guy in charge of making sure everything comes together. Tom Ridge is the newest person on the team.

Nick Capodice: [00:18:33] It sounds like a recipe for utter chaos.

Christina Phillips: [00:18:36] Yeah, that press conference showed that.

Tom Ridge: [00:18:37] If we think we've overlooked something, I make the call.

Nick Capodice: [00:18:45] So how do we get from an Office of Homeland Security to the creation of this massive department?

Christina Phillips: [00:18:51] It was later clear to many people that this solution an Office of Homeland Security with Tom Ridge as the director, wasn't enough. Agencies involved in national security were spread across departments with separate missions, and coordination wasn't happening as well as it needed to. In the months after the attacks on September 11th, as the government had to grapple with the major holes in national security, as the public had united around President Bush and was seeking protection, Bush announced the plan to establish a new cabinet Department of Homeland Security.

Christina Phillips: [00:19:24] I've been thinking of it like a bucket, the Homeland Security bucket, if you will. There would be twenty two agencies from other department buckets and they were going to be new agencies put in there. But that bucket didn't have everything.

Nick Capodice: [00:19:38] So Homeland Security wasn't this catch all. There's still work happening in other agencies that had to do with national security that weren't in the department.

Christina Phillips: [00:19:45] One of the major things that was not put in the Homeland Security bucket was the intelligence community, the Justice Department, FBI, CIA. So President Bush had to distinguish how the Department of Homeland Security would fit in with those other agencies.

Eileen Sullivan: [00:20:00] Dhs is primarily a law enforcement agency. It is enforcing the laws that the administration argues for in the Congress passes. And so they're not necessarily coming up with the laws. They're just but they are. They are enforcing them.

Christina Phillips: [00:20:16] This is Eileen Sullivan. She's the New York Times correspondent for the Department of Homeland Security.

President Bush: [00:20:21] Tonight, I propose a permanent cabinet level Department of Homeland Security to unite essential agencies that must work more closely together. Among them the Coast Guard, the Border Patrol, the Customs Service, immigration officials, the Transportation Security Administration and the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Employees of this new agency will come to work every morning knowing their most important job is to protect their fellow citizens.

Nick Capodice: [00:20:50] So have we reached the moment when you can explain what this whole new department looks like?

Christina Phillips: [00:20:54] Yes, it is time to pull out the giant whiteboard where I mapped out which agencies were absorbed into Homeland Security and how they fit into the purpose of the department, which President Bush very helpfully broke down into four different missions.

Nick Capodice: [00:21:08] By the way, we'll make sure to include a photo of this beast of a whiteboard on our website so you can follow along if you want at civics101podcast.org. Let's go through them one at a time. Tell me about mission number one.

Christina Phillips: [00:21:19] Mission number one is border control.

President Bush: [00:21:22] This new agency will control our borders and prevent terrorists and explosives from entering our country.

Christina Phillips: [00:21:28] Remember how I said there were four missions? Yeah, well, this first mission also has four different agencies in it focused on protection, enforcement and security at the border.

Nick Capodice: [00:21:36] So I see here the first one is U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Is that a new agency?

Christina Phillips: [00:21:42] Yes. So it's a new agency that absorbed customs and immigration agencies from the Treasury and Justice Department, as well as plant and animal inspection from the Department of Agriculture.

Nick Capodice: [00:21:51] So basically, like everything that comes across the border.

Christina Phillips: [00:21:54] Yeah, everything.

Christina Phillips: [00:21:55] The second agency is U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which is also known as ICE, and this is also a new agency. It's created specifically to protect the U.S. from cross-border crime and illegal immigration.

Nick Capodice: [00:22:07] Number three is another new agency under this border control mission the Transportation Security Administration. The TSA, which, as we already mentioned, did not exist before nine eleven.

Christina Phillips: [00:22:18] Yeah, this is the new law enforcement arm that puts airport security directly in the hands of the government.

Nick Capodice: [00:22:23] And the final part of the first mission of border control is the U.S. Coast Guard, which I always thought was part of the military.

Christina Phillips: [00:22:30] Yeah, it depends. The Coast Guard is technically overseen by the Department of Homeland Security and Peace, Peacetime and the Navy in wartime. Ok. It's not a simple system, especially considering that we've spent the majority of the 20 years since 9/11 at war.

Nick Capodice: [00:22:44] Ok, that's mission one. What's Mission two?

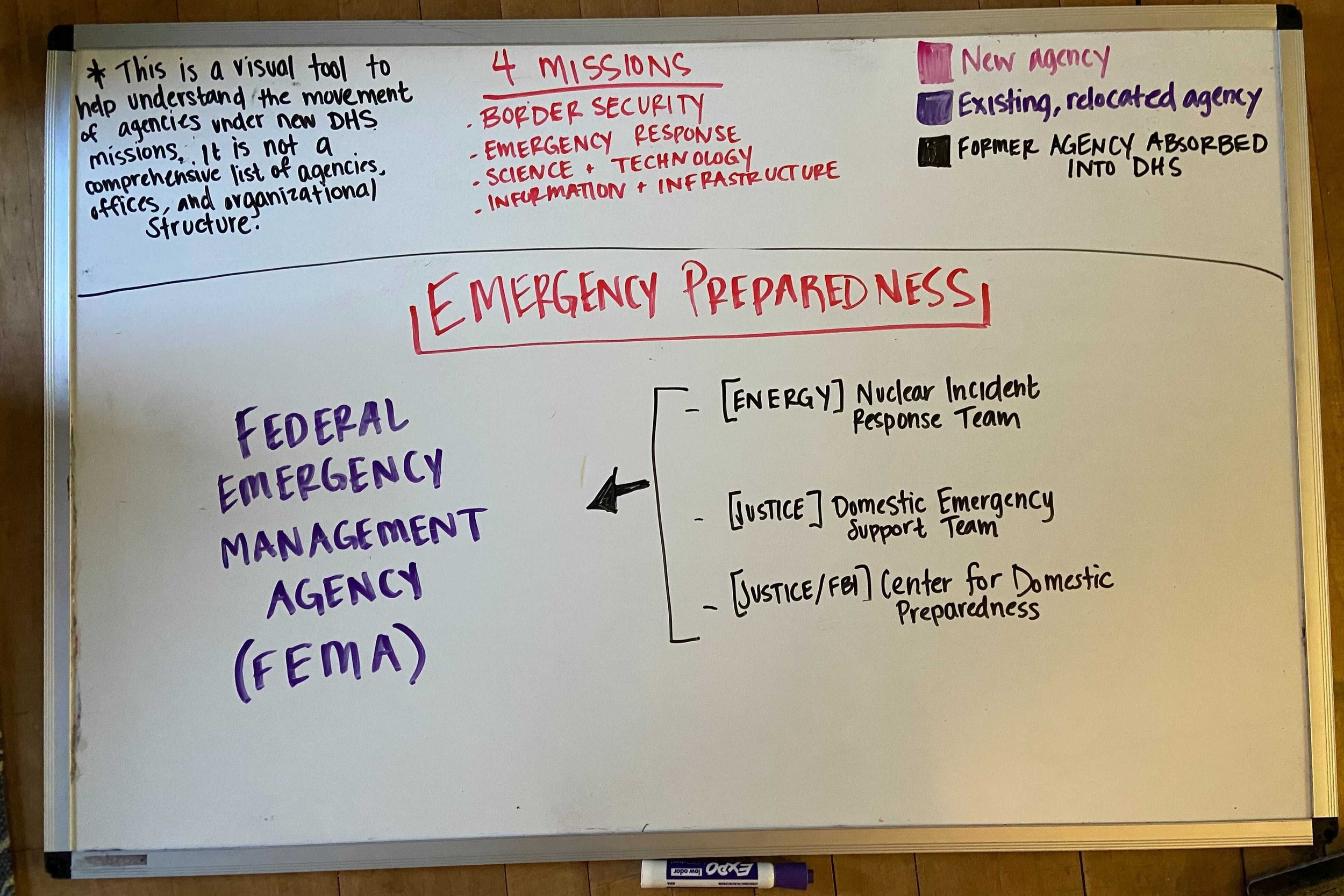

Christina Phillips: [00:22:46] Emergencies.

President Bush: [00:22:47] It will work with state and local authorities to respond quickly and effectively to emergencies.

Christina Phillips: [00:22:53] This is the Federal Emergency Management Administration, or FEMA, which was designed to coordinate disaster response between local and federal agencies. And it did exist before 9/11. But under the new reorganization, there was an additional focus on coordinating the response to terrorism related disasters.

Eileen Sullivan: [00:23:13] One of the original concepts of Homeland Security was that it would be the one to talk to state and local officials about about threats and about what they need to know. And so instead of getting multiple reports from different federal agencies, it should all be one.

Christina Phillips: [00:23:30] Homeland Security absorbed FEMA and FEMA absorbed the nuclear incident response team from the Department of Energy, the domestic emergency support team from the Department of Justice and the Center for Domestic Preparedness from the Justice Department and the FBI.

Nick Capodice: [00:23:43] Wow. So Mission Two: Emergency response. What about Mission Three?

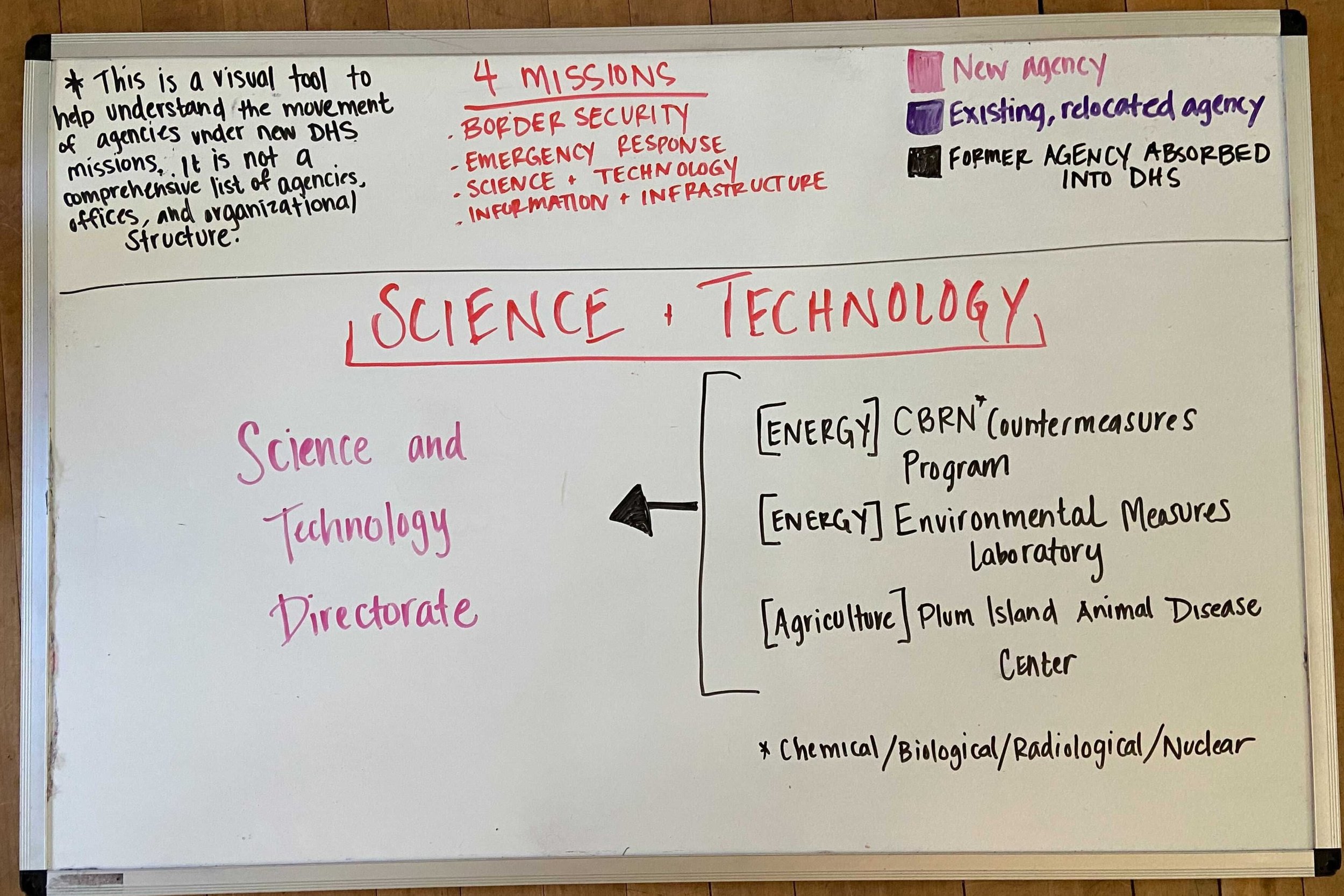

Christina Phillips: [00:23:49] I'm not sure I can actually summarize this one into a couple of words. Let's just listen to President Bush.

President Bush: [00:23:54] It will bring together our best scientists to develop technologies that detect biological, chemical and nuclear weapons and to discover the drugs and treatments to best protect our citizens.

Nick Capodice: [00:24:05] I'm going to bite my tongue about the nuclear thing. Tell me, what is Bush saying here?

Christina Phillips: [00:24:10] From what I can tell, this is the research and development arm of Homeland Security, but it's basically six different things. What's it called?

Christina Phillips: [00:24:17] The Science and Technology Directorate Directorate.

Nick Capodice: [00:24:20] Can you give me some examples of what a directorate actually looks like?

Christina Phillips: [00:24:25] So one thing the directorate has done is develop technology that helps first responders communicate effectively in emergencies. The directorate also works a lot with private companies that are developing the technology. The government may want to use things like security technology for screening people and goods or threat forecasting.

Nick Capodice: [00:24:42] Ok. Mission Three: Science and Technology Directorate. What's mission four?

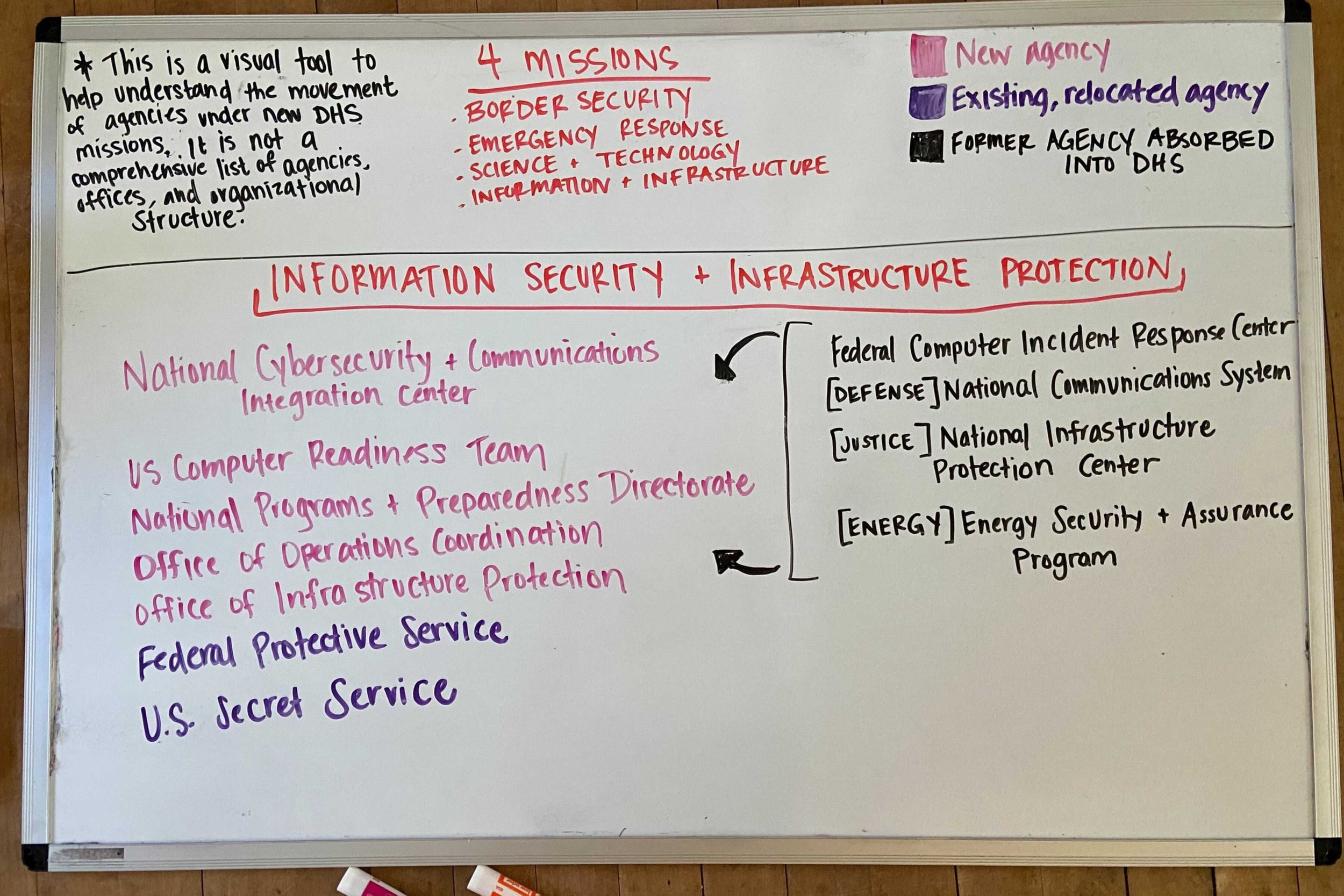

Christina Phillips: [00:24:46] Information analysis and infrastructure protection.

President Bush: [00:24:50] And this new department will review intelligence and law enforcement information from all agencies of government and produce a single daily picture of threats against our homeland. Analysts will be responsible for imagining the worst and planning to counter it.

Nick Capodice: [00:25:05] So cybersecurity and data gathering. But I also see the Federal Protective Service, which I don't know anything about, and the U.S. Secret Service, which I do, are also in this umbrella.

Christina Phillips: [00:25:15] Yeah, I had to look this up to the Federal Protective Service is the law enforcement that protects federal properties around the U.S. like federal courthouses and post offices.

Nick Capodice: [00:25:23] And the Secret Service, which was initially created to combat counterfeiting, provide security for the president, vice president, White House. But they still do investigate crimes against the U.S. financial system. With the reorganization, this massive Cristina, I assume it's not as simple as telling all these people, OK, you used to work for this department and now you're being moved to another department and your new mission is to protect the American people and prevent terrorists from killing Americans.

Christina Phillips: [00:25:52] One of the biggest hurdles for the department was Congress, specifically congressional oversight. See, in our system of checks and balances, one check on the power of the executive department is congressional committees. They monitor the work being done in the executive branch, and that work didn't stop when agencies were moved into a new department. Here's Eileen Sullivan, the Homeland Security correspondent for the New York Times.

Eileen Sullivan: [00:26:15] So while the agencies were pulled from their parent departments and formed DHS, the Congress didn't really give anything up.

Christina Phillips: [00:26:26] At the start, all the committees that were overseeing those individual agencies continued to oversee them under Homeland Security. It was over a hundred different committees by some count, 123.

Nick Capodice: [00:26:36] How does that number compare to other departments?

Christina Phillips: [00:26:39] Well, the Department of Defense, which is the largest cabinet department, is overseen by 30 committees. At one point, Secretary Chertoff, who was appointed in 2005, said that the department had written over 5000 briefings and attended over 300 hearings for Congress in a single year,

Nick Capodice: [00:26:55] And has that number changed since.

Christina Phillips: [00:26:57] Over the years, the number of committees have been winnowed down to around 90.

Nick Capodice: [00:27:01] So not much change at all,

Eileen Sullivan: [00:27:02] Which just shows you how difficult it is to take away turf anywhere, ever.

Christina Phillips: [00:27:08] And that kind of turf battle was bad, even when the focus of the department was still pretty narrow.

David Schanzer: [00:27:13] Well, first of all, there was really an almost exclusive laser like focus on the threat from Al Qaida and other like minded groups.

Christina Phillips: [00:27:22] That's David Schanzer, who was working in Congress on Homeland Security in the early years of the department.

David Schanzer: [00:27:27] Another nine 11 style attack where people or weaponry or explosives or weapons of mass destruction could be smuggled into into the U.S. and deployed.

Nick Capodice: [00:27:39] So what happens when time goes on and the focus isn't so laser like? What changed over the next 20 years?

Eileen Sullivan: [00:27:47] Current events have kind of defined each chapter of the department.

Christina Phillips: [00:27:51] As the department has encountered new challenges and new leadership. Its mission has evolved. There have been some major failures, like in 2005, when Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast and in each successive administration after Bush, the commander in chief, appointed heads of the department that fulfilled their agendas. You can see over time how the department's power has been applied in new ways, determined by what the government and its leader consider the biggest threats to our country. For example, President Obama made border security and cybersecurity. His major focuses during his presidency. He about doubled the number of Border Patrol agents and unmanned aerial vehicles, also known as drones, that surveyed the border.

Nick Capodice: [00:28:32] And then what happened under President Trump?

Christina Phillips: [00:28:33] He wanted to limit who was allowed to enter the United States legally or not. This included his highly controversial executive actions that restricted travel to the U.S. for citizens from several majority Muslim countries.

Archival Audio: [00:28:45] Protesters gathered outside JFK International Airport in New York and demanded the release of refugees blocked from entering the United States.

Christina Phillips: [00:28:53] And under President Trump, the federal government also enforced a family separation policy at the U.S.- Mexico border.

Archival Audio: [00:28:59] Border Patrol officials said today that since April, more than 2300 children have been separated from their families, with some held in makeshift tent cities.

Nick Capodice: [00:29:08] And what's most interesting to me is that the Department of Homeland Security was specifically created to help prevent something like 9/11 from ever happening again. But with each successive administration, it's become much more than that.

Christina Phillips: [00:29:24] This is a story of what happens when the way our government does things is held up to a microscope in a moment of violence and pain. Pair that with a public united by fear, anger and patriotism, and the outcome is a massive reorganization under a short timeline where the government is trying to protect the nation as its writing its own manual on what that actually means.

Christina Phillips: [00:29:49] The Department of Homeland Security has given us a name for our feeling of safety and security the homeland and has drawn lines around the borders of safe and dangerous. And in the 20 years since, given our leaders the tools to enforce them, from cybersecurity to law enforcement at the border, to screenings at the airport.

Christina Phillips: [00:30:17] So that's it for the Department of Homeland Security. This episode was written and produced by me, Christina Phillips, with help from You Nick Capodice and Hannah McCarthy.

Nick Capodice: [00:30:25] Our staff includes Jacqui Fulton. Rebecca Lavoie is our executive producer.

Christina Phillips: [00:30:28] Music In this episode by Audiobringer, Broke for Free, KiloKaz, Martin Skeleton's Blue Dot Sessions, Makiah, UNCan, Chris Zabriskie, Jason Leonard and Yung Kartz

Nick Capodice: [00:30:40] Civics 101 is a production of NHPR, New Hampshire Public Radio.