What does it take to be born an American citizen? And then, once you are, how do you prove it? And what does it get you?

We talk to Dr. Mary Kate Hattan, Dan Cassino, Susan Pearson and Susan Vivian Mangold to find out where (American) babies come from, and what that means.

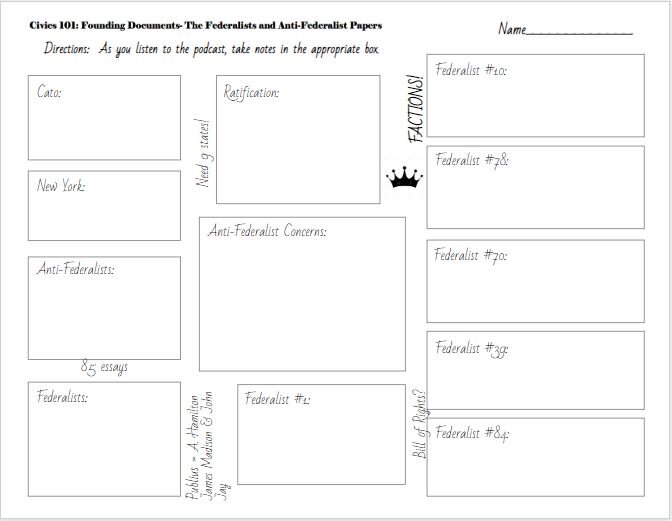

Click here to get a Graphic Organizer for notetaking while listening to the episode.

Episode Segments

TRANSCRIPT

Hannah McCarthy [00:00:08] I want to start this episode at the very beginning.

[00:00:16] Of everything. I mean I want to start this episode the way everybody starts.

Mary Kate Hattan [00:00:25] I love that moment when you see a mother or a family meet their newborn for the very first time after all these months of anticipation. I continue to find it to be one of the most moving things I have ever been lucky enough to be present for.

Hannah McCarthy [00:00:43] This is Dr. Mary Kate Hatten. It's such an honor to be there. We'll never get old for me.

[00:00:51] Mary Kate is a family medicine physician who practices obstetrics at Concord Hospital in New Hampshire. She cares for pregnant mothers. She delivers babies and ideally she becomes that baby's doctor once they enter the world.

Mary Kate Hattan [00:01:04] I think most people are amazed that in the end the most important part is when you actually meet your baby. And sometimes I think those moments when you first realize Oh my goodness there's this whole baby I need to take care of. I think sometimes that can be surprising.

Hannah McCarthy [00:01:20] So Nick, you have experienced this moment twice.

[00:01:24] The birth of a new baby.

[00:01:26] Did did you feel like instinct kicked in or were you a little...

Nick Capodice [00:01:31] Absolutely terrified. I couldn't believe I couldn't believe they let me take it home. She. Couldn't believe they let me take it home in the car after he was born.

Hannah McCarthy [00:01:39] So you had no idea what to do.

Nick Capodice [00:01:42] I'd read a lot of books.

[00:01:44] I had a lot of people's advice but when it's the real thing yeah I didn't know what to do.

Hannah McCarthy [00:01:48] Well luckily even if you are one of the many parents who don't immediately know what to do with this tiny human you're responsible for there are systems in place to make sure that that baby gets off on the right foot.

[00:02:07] Mary Kate made clear that there are plenty of ways to have a baby in theU.S. but best practices dictate important steps for doctors and nurses to take.

Mary Kate Hattan [00:02:16] So after her baby is delivered were immediately making sure that the baby's breathing that the baby has a nice tone and is able to move. We're hoping that the baby cries and we check that both at the first minute. The baby's been born and again at five minutes to help give an idea of how the baby is transitioning as it's delivered.

Hannah McCarthy [00:02:39] I love this idea that this human enters the world and immediately there's this transformation going on because they're adapting to life on the outside. And meanwhile the person or people who brought this child into the world they are adapting to my role as your physician is to make sure I tell you the up to date guidelines and recommendations and to tell you.

Mary Kate Hattan [00:03:03] What we consider to be safe to practice and how to keep your babies thriving and healthy. But ultimately we're a team. And parents know what's important for their child. And I trust parents instinct. And while I can advise them medically on things I also trust that they love that child and that they're going to work with me to let them know what's working and where they need more support and for things that they may not be working for them.

Hannah McCarthy [00:03:28] So doctors like Mary Kate are going to make sure that the baby's eating trying to coach the mother through breast or bottle feedings monitoring for jaundice weight gain making sure the parents have a car seat making sure that that baby can breathe in that car seat and if this baby is born in America.

[00:03:48] While there are a lot of other gears that start to grind but before we pull back the curtain on starting your life in the United States. Care to introduce yourself my fellow American?

Nick Capodice [00:04:04] I'm Nick Capodice.

Hannah McCarthy [00:04:05] And I'm Hannah McCarthy and today kicks off the first in our six part series on bureaucracy and you.

Nick Capodice [00:04:11] Our Civics, ourselves, if you will.

Hannah McCarthy [00:04:14] It's the way that government that law the institutions interact with you mold you shape you control you and help you over the course of your lifetime from birth.

Nick Capodice [00:04:28] To death.

Hannah McCarthy [00:04:33] And today we're gone. Brass tacks absolute basics. The facts of American life before you lived very much life at all. Facts like I can't name my baby. The exclamation marks I'm.

[00:04:46] Actually naming laws vary from state to state so that's kind of a case by case basis kind of thing. And anyway the name is not nearly as important to being an American as the circumstances of your birth.

Nick Capodice [00:04:59] So where you're born and who your parents are.

Hannah McCarthy [00:05:02] Exactly. And it may sound obvious but those facts mean everything in the US.

Dan Cassino [00:05:09] So this goes back to the 14th Amendment.

Hannah McCarthy [00:05:10] Say hello to Mr. Dan casino Professor of Political Science at Farleigh Dickinson University. He is also a generous repeat guest on the show. The reconstruction period after the Civil War ended up defining citizenship because we changed the constitution in a really major way back then.

Dan Cassino [00:05:29] The Civil War movement the 13th 14th and 15th amendments.

[00:05:32] And these are they are in order to try and protect the rights of freed slaves in the southern states and make sure the southern states treat everyone equally because obviously they didn't want to. That's why we had a civil war.

Nick Capodice [00:05:42] How did the Reconstruction Amendments apply to babies being born today. Those amendments were designed to treat a very specific problem right.

Hannah McCarthy [00:05:50] They were.

[00:05:51] But in fixing that problem we changed something huge after the emancipation of thousands of enslaved people. There was this problem. These people had been counted as three fifths of a person before the Reconstruction Amendments but they were not citizens they didn't have any rights. Then Congress passes an amendment saying OK slavery is now illegal. So we've got a bunch of free Americans their citizens right.

Dan Cassino [00:06:22] So the state of Georgia could decide who's a citizen of Georgia and who's not. And of Georgia gives certain rights to citizens of Georgia we don't give to noncitizens of Georgia. Why does that matter. The fear was after the Emancipation of the slaves the state of Georgia was gon decide all those newly freed African-Americans while they might be federal citizens but they're not citizens of Georgia. So we don't have to give them any rights under the state constitution of Georgia.

[00:06:44] So the 14th Amendment is trying to get rid of that possibility.

Hannah McCarthy [00:06:46] The 14th Amendment shows up to say look everybody who is born in the United States is a citizen of both the United States generally and the state in which they reside.

Nick Capodice [00:06:58] So before that what made you a citizen.

Hannah McCarthy [00:07:01] That was actually up to the states which is why there was that risk that proslavery states would deny citizenship to newly freed people. But after the 14th Amendment.

[00:07:11] If you're born here you're a citizen.

Nick Capodice [00:07:16] So this is a birthright citizenship right. Is that what we call it.

Hannah McCarthy [00:07:19] Exactly. Citizenship is your birthright if you're born on American soil or to American parents for the most part. There are some exceptions having to do with how long your American parent resided in theU.S. or was working for theU.S. abroad. Also Nick Here's a wacky one a person is a citizen. If they are of quote unknown parentage found in theU.S. under the age of five. And if nobody can prove they were born elsewhere before they reach the age of 21.

Nick Capodice [00:07:49] How often does that happen. How many people achieve citizenship that way. It sounds almost Dickensian but so it sounds like your very best bet is being born onU.S. soil.

[00:07:59] Yes but that is an aspect of birthright citizenship that people debate heavily because there are a lot of people who feel like noncitizens use birth onU.S. soil as a way to game the system.

Dan Cassino [00:08:15] Well because it means that if you are not a citizen and you show up the United States and you have a baby that baby is a citizen and there's nothing anyone can do about that as long as they're born in the United States. And this has led to a growth of what's called birth tourism in the United States. We're well here foreigners from around the world come the United States and Saffren birthing suites hospitals in major cities and give birth there in order to give their child a chance at Americans is when that child becomes an adult.

Nick Capodice [00:08:41] But to be clear it isn't actually gaming the system it's the law it's totally legal.

[00:08:46] And right now in the U.S. babies born here ge tU.S. citizenship.

Hannah McCarthy [00:08:49] Yes except for the babies of foreign diplomats there's this clause in the 14th Amendment that says you're a citizen if you're born in theU.S. and quote subject to the jurisdiction thereof. But foreign diplomats are not subject toU.S. courts or authorities they have diplomatic immunity.

[00:09:08] All right. So not subject to the jurisdiction thereof equals not a citizen but if we're looking at a non diplomat's baby born on American soil we are looking at an American baby. Even though people argue about the correct like being swaddled in an American flag.

Hannah McCarthy [00:09:24] Or like have you ever played the Sims?

Nick Capodice [00:09:27] A little bit.

Hannah McCarthy [00:09:28] You know that green diamond that floats over their heads?

Nick Capodice [00:09:31] What's that called?

Hannah McCarthy [00:09:32] It's called the plumb bob.

Nick Capodice [00:09:33] An American plumb bob.

Hannah McCarthy [00:09:34] An American plumb bob floating over your head except your plumb bob is invisible because you know yeah you've got citizenship but you can't actually enjoy it until someone makes it official.

Nick Capodice [00:09:50] So you can be a U.S. citizen but not actually get any of the benefits of being a U.S. citizen.

Hannah McCarthy [00:09:54] Right. Because how can I know that you're really a citizen.

[00:09:58] I mean I got to have it in writing.

Nick Capodice [00:10:02] When you're born the first thing you have to do is register the birth with the government to let the government know that someone has been born here and generate a birth certificate from that and that person is a legal document.

Nick Capodice [00:10:12] It's kind of like if a tree falls in a forest does anybody hear it.

Hannah McCarthy [00:10:16] Right. In this case if no one writes it down authorizes it. The question is did it really happen.

Susan Pearson [00:10:23] So if you have no birth certificate and you are not white you are much more vulnerable.

Hannah McCarthy [00:10:32] This is Susan Pearson. She's a history professor at Northwestern University and she's working on a book about birth registration in the U.S.

Susan Pearson [00:10:40] Right. You are vulnerable. If something goes wrong if you're picked up by the police to deportation. Although we have near universal birth registration in theU.S. the more on the margins you are the less likely you are to have your birth registered.

Nick Capodice [00:10:59] So she's talking about American citizens getting deported.

[00:11:02] Does that happen.

Hannah McCarthy [00:11:03] It's actually estimated that thousands of Americans are detained or deported every year in theU.S. And your role honorable enough just having a certain last name or looking a certain way but if on top of all that your American birth was never registered. You are in real trouble. How do you prove that you're a citizen. There is this pretty well known story of a young woman in Texas whose birth was unregistered and who had very few official records of her life.

Alicia Faith Cunningham [00:11:32] My name is Alicia Faith Cunnington and I'm aU.S. citizen by birth. However I was born at home and my parents neglected to file a birth certificate for a birth record of any kind. They also never got me Social Security number.

Hannah McCarthy [00:11:46] Now in Alicia's case immigration is not exactly breathing down her neck. She is a white woman. However she can't get a passport she can't get a driver's license.

Susan Pearson [00:11:57] Her home state of Texas as a result of her case ended up passing a law which basically made it a criminal offense for parents not to register their children's birth.

Nick Capodice [00:12:12] Alright for some people there's this threat of deportation.

[00:12:14] And they're not able to get a passport driver's license or Social Security card.

Hannah McCarthy [00:12:18] Also think about all of the other inconveniences that could crop up a birth certificate doesn't just prove that you're a citizen. It proves your age and think about all of the age restrictions in the U.S. At 16 you can go to adult prison at 18. You can vote at 21. You can drink at 35 you can run for president without your birth certificate. Legally speaking you do not have an age. But if you go back even 100 years in the U.S. the whole age thing is not as big of a deal.

Susan Pearson [00:12:51] A lot of people in the 19th century and even into the 20th century actually didn't know exactly how old they were and didn't actually know exactly what their birthdays were or what their children's birthdays were.

Hannah McCarthy [00:13:05] Or if you did bother to make note of your child's birth it was probably in the family Bible or maybe your church took note of the day when your baby was baptized. But it wasn't exactly an official document.

Nick Capodice [00:13:17] What about the president thing you have to be 35 years old that's in the original Constitution. And aren't there age requirements for senators and reps and that sort of stuff.

Hannah McCarthy [00:13:25] There are. But then again when the framers wrote the Constitution they weren't expecting anyone other than wealthy white literate landed gentry to end up in office. And at the time if anyone was having their birth recorded it was those upper class people.

Nick Capodice [00:13:41] So possessing the knowledge of your age is like defacto privilege of its own back in the day. Like the framers probably knew their own birthdays right.

Hannah McCarthy [00:13:49] And then the cobbler let's say who made James Madison shoes he might be able to estimate his age based on family lore and rough dates. It's like the further away you get from privilege and power the further you get from that specific birthday.

Susan Pearson [00:14:05] Frederick Douglass the famous abolitionist and escaped slave begins his autobiography by saying that he doesn't know when he was born and that slave owners kept this information from their slaves and that this was for him evidence of the way that African-Americans under slavery were treated like chattel like animals right and not like human beings. But in reality a lot of plantation owners actually did keep records of the births and deaths of their slaves.

Hannah McCarthy [00:14:48] So even though not really knowing your age was not uncommon. There is something special about age even in the early United States withholding birthdays even when they knew exactly when an enslaved person was born was a way for slave owners to further strip that enslaved person of identity and power and access because age does have this elevated status in our Constitution.

Susan Pearson [00:15:19] Voting. Serving in elective office serving on a jury. Those kinds of things that we understand as being sort of primary ways that we would distinguish a democracy from another kind of form of government.

[00:15:35] Those are actually all bounded by age. Even before there's birth registration and therefore a really easy way for people to show how old they are. We already have rules about what you can and can't do as a citizen based on your age right.

[00:15:54] I'm thinking about today and we often use age as this marker for what you can't do but you can't get married or drive a car or work most jobs. If you're under a certain age when did that all start.

[00:16:05] Child labor laws start getting passed again this starts in New England like birth registration does in the middle of the 19th century. As soon as you start having really. Factory labor. And you know the factories of the mid 19th century or not the factories of the 20th century but people start to get a little worried about you know is it good for their bodies to be in these more dangerous working environments.

Hannah McCarthy [00:16:31] So we started to look at little kids working in mills and being horribly injured and we started to think you know what maybe we shouldn't let those little kids work in those mills. But change came slowly.

Susan Pearson [00:16:44] I mean most of the earliest child labor laws had no provisions for proof of age in them at all he would just say something like You know you can't work in the cotton mill unless you're over the age of 14.

[00:16:57] And so people would just show up and whoever's doing the hiring at the mill would say well how old are you. Zahm for two you'd say whatever the law said right. I mean it might be true or it might not.

[00:17:10] And they say Okay!

Nick Capodice [00:17:13] That makes no sense. What have you ever particularly tall or strong 11 year old and mom and dad are quite sure how old they are so they might as well say 14 so the good can get to work.

Hannah McCarthy [00:17:22] Exactly that's the problem. That age requirement is all well and good but it doesn't mean anything if you don't actually know how old you are. Or if people can fudge the numbers which they do and that's around the time the National Child Labor Committee starts ramping things up.

Susan Pearson [00:17:39] And they think that a lot of children are working under age in factories right.

[00:17:44] And so they press states to pass laws that are little more stringent that have some kind of enforcement mechanism that have some kind of system where instead of just walking into the factories hiring office and saying OK I'm here and the supervisor being late great. You know here's a broom go sweep the floor. They want to say that the child has to present.

[00:18:07] Some kind of proof of their age. And in most places this is an affidavit of age which is supplied by going to a local notary public.

Hannah McCarthy [00:18:20] Close to a birth certificate but no cigar.

[00:18:23] It ends up being basically the same situation as before mom and dad can just say little Janie is 14.

Susan Pearson [00:18:30] But then there was this big investigation in 1895 in New York City done by the state legislature. There was a widespread feeling among again Child Labor opponents that this function was no better than parents walking into employment offices with their kids right because notaries are getting paid for performing the service. They don't care. They're not law enforcement officers. They want to get their 25 cents and their view of their job is I don't decide the truth I just certify that a person said this to me. Right. So there's this big exposé of the notary system and child labor opponents really begin to press for what they call documentary proof of age.

Nick Capodice [00:19:24] I love a good exposé. They get things done.

Hannah McCarthy [00:19:27] Yeah this one is no exception. Child Labor opponents took a long hard look at the system and they decided that they knew what to do. There's only one way to ensure an accurate age for a kid a baby must be registered when they are born.

[00:19:42] And in a narrow window, too.

Susan Pearson [00:19:43] Could be three days it could be three months but the point is that there's no incentive for anyone to lie at the time that a birth is registered right. You're not thinking well if you know 12 years from now I'm going to want to say that Jaynie is 14 and not 12. Right. The other thing about birth registration laws is that in most places they make the duty to report the birth. The job of the birth attendant.

Hannah McCarthy [00:20:19] The system isn't perfect right. For example there were a lot of immigrants coming to theU.S. at this time and they were out of luck when it came to proving their age and the race listed on a birth certificate was a weapon in the hands of those who sought to disenfranchise people of color in theU.S. but ultimately we did get to nearly 100 percent of births being registered in this country.

Nick Capodice [00:20:42] Nearly but that nearly kind of trips me up because at this point in American history that birth certificate is the golden ticket. Right. I mean that not only does it help keep you safe from deportation. It also helps get you a license passport register for school get married get a Social Security card.

Hannah McCarthy [00:20:59] Yes. Also by the way the social security card that is another big one in terms ofI.D. in theU.S. And so there's this box that you can check off when you get your birth certificate and the Social Security Administration will send you one. But if you missed that boat you end up having to prove your citizenship in another way to get a delayed social sometimes or religious or hospital record is enough. But that can be a real catch 22.

Nick Capodice [00:21:23] OK so do we have a right to birth certificate. Are my rights being violated if my parents don't register me.

Susan Pearson [00:21:28] I mean it's it's so basic to be able to establish who you are. Right. And so for parents to deny that to children it comes to be seen as almost as criminal and in fact theU.N. has a charter of children's rights which was passed in 1938.

Nick Capodice [00:21:46] Yeah but that's the U.N. I mean it's not our Constitution.

Hannah McCarthy [00:21:52] Well no this is actually a state's thing. So all states have some kind of language in their statutes that requires a physician midwife parent or some other person present at a birth to register the birth of that child usually within five to ten days in some cases. If a doctor or a midwife fails to do this they can have their license suspended until they register that baby.

[00:22:15] But there are still people who don't register their child's birth for other reasons.

Susan Pearson [00:22:21] They're part of the sovereign citizen movement right. And they say are people who see a kind of very libertarian. You write that you see registering your birth as a form of submission to the state that is illegitimate.

[00:22:36] And that is giving up a piece of your autonomy in a piece of your sovereignty.

Hannah McCarthy [00:22:41] It's not just disenfranchised or marginalized or poor or rural populations that may be susceptible to not receiving a birth certificate. There are people out there who say look you can't make me submit to the government and you can't make me force my child to do that either. But some of these kids do grow up wanting a birth certificate for various reasons they might want to get a legal job or travel for instance. But it's much harder to prove where and when you were born when you're 18 years old.

Nick Capodice [00:23:16] It's amazing to me that this piece of paper this hallmark of boring bureaucracy is like the key to the whole city. But what do you get for that.

[00:23:26] If the birth certificate is the key to protections and privileges what are those protections privileges.

Hannah McCarthy [00:23:32] Like right out the gate.

[00:23:34] What do you get the minute you come wailing into this world?

Nick Capodice [00:23:38] Yeah.

Hannah McCarthy [00:23:38] OK. Day one. You're a brand new person here in theU.S. What does that make you in the eyes of the Constitution?

Susan Mangold [00:23:45] Children have rights as citizens of the United States. And then they have some rights even when they're not citizens of the United States based on case law or statutory law rather than constitutional law.

Hannah McCarthy [00:24:00] This is Sue Mangold chief executive officer of the Juvenile Law Center. It's a nonprofit that advocates for the rights of children in theU.S.

Susan Mangold [00:24:08] So usually when you try to understand the constitutional rights of children you begin with a series of Supreme Court decisions. Meyer Prince Pierce Yoder.

Hannah McCarthy [00:24:23] The interesting thing about these cases is that they weren't actually brought on behalf of the children. They're about what and how a teacher can teach her how a parent or guardian raises a child. Because when it comes to what you get as this new young person in America a lot of that has to do with the adults around you. What are their rights when it comes to you.

Nick Capodice [00:24:46] They're pretty limited aren't they?

Hannah McCarthy [00:24:48] Yes and No.

[00:24:49] You solve this principle of a parent raising a child as they see fit.

Susan Mangold [00:24:55] This balance between parental rights children's rights and state's obligations. And so you know there's a whole line of cases around states being able to order medical care and it's more or less limited to when you know the medical care is widely approved and is lifesaving. But there's you know cases on the margins that don't require quite as high a standard. And in terms of education parents can educate children at home they can send them to private schools they can send them to public school. But there are quite extensive state regulations even of home schooling. And so the parents can make choices but they are limited again.

Hannah McCarthy [00:25:42] Sue describes this triangle of parents rights children's rights and states rights and children's rights have a lot to do with not being abused and not being neglected and also being educated. And the states are the ones who enforce those rights.

Nick Capodice [00:25:58] What if somebody under the age of 18 decides her parent is just not for them. Can they divorce their parents?

Hannah McCarthy [00:26:06] They can. That would be emancipation.

Susan Mangold [00:26:08] Children seek emancipation all the time. They seek access under a range of laws that give them access to health care and reproductive health care mental health care and addiction services without their parents consent. Mindful that their parents would not consent but the laws for all kinds of public health reasons give the child their own right to seek the services even if they're well below the age of 18. And again that depends on the state's laws.

Nick Capodice [00:26:57] It seems like the story of children's rights in the U.S. At its simplest is about our understanding children as hokey as that might sound.

[00:27:08] Like we went from looking at them as many adults to thinking of childhood as this separate stage of life thinking. Maybe that means they shouldn't operate heavy machinery in a mill or get married. Finally realizing they need extra defence against abuse and neglect. It's taken hundreds of years. Which is funny because people think you're just going to magically know what to do and you have a baby of your own. But as a nation. We still aren't really sure how to raise a kid.

Hannah McCarthy [00:27:39] No it's been slow progress. But being born in America.

[00:27:44] I think increasingly means that you're being looked out for. And I think there's also. An increasing attempt to listen to young people. Whether that's literally or by looking at their brains and development.

[00:28:00] And as with all shifts in our democracy when you give a group a voice the system starts to respond.

Nick Capodice [00:28:07] Yes and kids do have a voice. All right. That's actually one basic right. We didn't get to in this absurd.

Hannah McCarthy [00:28:14] Yeah I was kind of thinking that's better suited to an episode about schools.

Nick Capodice [00:28:19] I see where you're going here.

Hannah McCarthy [00:28:20] That's next time on civics 101.

[00:28:34] This was just the beginning. There's a whole lot of life to live here. It's Civics 101 and we're making our way through those life stages. Next stop school.

Nick Capodice [00:28:43] And there's a whole lot left to learn too. You can check out more information about being born in America and all of our upcoming episodes at Civics 101 podcast dot org.

Hannah McCarthy [00:28:52] This episode was produced by me and McCarthy with Nick Kapit each day our staff includes Jackie Helbert Ben Henry and Daniela Vidal Ali. Erika Janica is our executive producer.

Nick Capodice [00:29:02] Maureen McMurry really considers herself more of a citizen of the world.

Hannah McCarthy [00:29:05] Music in this episode by Shaolin Dub. The 126ers, TextMe Records, HiDi, Blue Dot Sessions, Frederic Chopin, and Johannes Brahms.

Nick Capodice [00:29:14] Civics 101 is a production of New Hampshire Public Radio.

Hannah McCarthy [00:29:19] Mom and Dad can just say little Janie is 14.

Nick Capodice [00:29:24] Janie! Mary, Janie! Don't you remember me? You know what that is right?

Hannah McCarthy [00:29:30] Yeah, that's a good Jimmy Stewart.

Nick Capodice [00:29:30] Now, I - I - I - I wanna make a boys camp. I wish I had a million dollars.

[00:29:39] Hot dog!